Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

On March 27, Daniel Kahneman, likely one of world's most influential psychologists, passed away. Despite having experienced the horrors of the second world war, he lived a rich life. Together with Amos Tversky (1997-1996), he managed to influence economists en masse to abandon a utility-model originating from the renaissance.

Academic people in social science relate to Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (1937-1996), but probably for different reasons.

Among most economists Kahneman and Tversky are considered behavioral economists, but in the field of psychology, they are psychologists.

“At the beginning of their careers, they worked in different branches of psychology: Kahneman studied vision, while Tversky studied decision-making”.Tversky was positive and confident and Kahneman the exact opposite. The differences made them very productive. At the same time, they published relatively few articles together. But all the articles became very influential (Sunstein and Thaler, 2016).

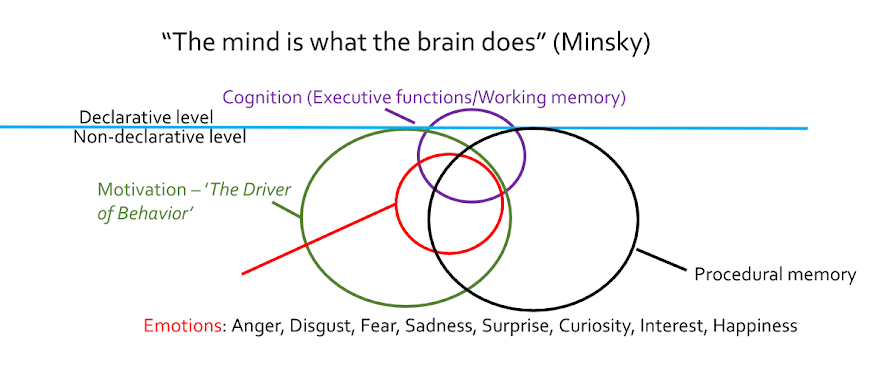

In order to understand their work, it's favorable to understand how the mind works, and how the understanding about how the mind works differed depending on your location, and also how that understanding changed over time.

When Kahneman, born 1934, and Tversky, born 1937, started to study psychology, most people likely associated psychology with the Austrian physician Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), or Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov's (1849 - 1936) behavioral approach.

“the first [cognitive] revolution occurred when a group of experiment psychologists, influenced by Pavlov, famous for his studies on salivating dogs, and other physiologists, proposed to redefine psychology as the science of behavior. They argued that mental events are not publicly observable” (Miller, 2003).But already in 1927, Cecil Alec Mace (1894 - 1971), industrial psychologist at Cambridge university published Sibylla; or the Revival of Prophecy. The introduction:

“Can prophecy be a science? Science, at any rate, appears to aim at prophecy. We are often told that the test of a hypothesis lies in the events that it predicts; but it’s a test that is much too rarely applied” ...During the 1930s, gestalt psychologists like Max Wertheimer (1880 - 1943), and his student Karl Duncker (1903 - 1940) worked on topics concerning productive thinking, that is, how members of our species simulate scenarios forward in time in order to reach a goal (a prospect) (Duncker, 1935, 1945; Wertheimer, 1945).

“And so another question occurs. What is the future of prophecy? Psychical research may even yet surprise us. Latent powers of divination may lurk in the human mind, but it is premature no doubt to look for enlightenment here. Less sensational but more significant is the emergence of the prophetic function in the work of science itself, and in the pedestrian progress of our general intellectual life in the twentieth century.”

In 1932, Frederic Bartlett (1886 - 1969), experimental psychologist, published his seminal work on memory, suggesting you can't trust it (Bartlett, 1932).

In 1935, Dr. Mace conducted the first study on goal-oriented prospection using inductive or experimental design. The result showed that assigned goals have a better impact on people's performance compared to abstract assignments like 'do your best' (Mace, 1935).

In 1950, Joy Paul Guilford (1897 - 1987), a psychologist known for his psychometric study of human intelligence was assigned to the role as president for the American Psychological Association (APA).

In 2007, I went on a one month visit to Buffalo, New York, to work with Dr Scott Isaksen, who served as advisor for my doctorate. In his office with green leather chairs at Grandview trail, Dr Isaksen told me some interesting anecdotes about Guilford.

Dr Isaksen was one of Guildford's students. As the story went, at the end of the lectures about psychometrics, most students had left.

Dr Isaksen also told me that Guildford was assigned the role as president of American Psychological Association (APA) to promote statistical analysis in the field of psychology.

For his address, Guilford wrote a paper where he discussed how factor analysis can be used to discriminate between intelligence and creativity.

With reference to Lewis Terman's and Melita Oden's work on intelligence, Guilford described intelligence as the ability to understand concepts and their inter-relations, whereas creativity was the ability to form new concepts.

Now, of course, there is some correlation between intelligence and creativity, but also significant differences. This is where factor analysis comes into the picture. But the paper wasn't label factor analysis, but creativity, and that's how people refer to it - a paper about creativity (Guildford, 1950).

Cliff-hanger.

During the 1950s, Polish gestalt/social psychologist Salomon Asch (1907 - 1996) conducted studies where the criteria was a mental fallacy called conformity. Dr Asch proposed, and demonstrated, that social influence will sway people's attitude away from a factual situation (Asch, 1956).

In the 1950s, the second [cognitive] revolution took place:

“If scientific psychology were to succeed, mentalistic concepts would have to integrate and explain the behavior data. We were still reluctant to use such terms as 'mentalism' to describe what we needed, so we talked about cognition instead” (Miller, 2003).1964, work and industrial psychologist Edwin Locke, continued the work Dr Mace had started almost thirty years before (Locke, 1964). Together with his colleague Gary Latham, Goal-setting theory was formulated (Locke et al. 1981; Locke and Latham, 2002). Goal-oriented prospection seems to be what normal thinking is about (Gilbert & Wilson, 2007; Kaku, 2014).

Its likely that Kahneman's and Tversky's work was an extension, and a mix of, the work conducted by Asch, Bartlett, Duncker, Mace, Wertheimer and many others in the same tradition, that is, trying to understand the validity of a prophecy, and how our memory system disrupts the 'mentalistic' processes involved in running scenarios forward in time.

“We study natural stupidity” (Tversky).

Here's a list of there most famous models:

Representative bias (Kahneman & Tversky, 1972), e.g. the delusion that eating fat makes you fat. In reality, we really need to eat [animal] fat, e.g., for brain health (Ede, 2019).

Availability bias (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973), e.g., the delusion that information that is easy to imagine and that is repeated also is true. Example, when mainstream media reiterate that the world is warming rapidly. In reality, since the Eocene, the world is in a state of peak cold.

Simulation bias (Kahneman & Tversky, 1977), reminiscent of the above - that we use the first available mental representation as explanation, e.g. when thinking about domestic violence, assume that the typical perpetrator is a man. In reality, the typical perpetrator of domestic violence is a woman.

Prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), e.g., our species' inability to apply goal-oriented prospection, due to interruption of constructive memories. The typical example is the suppression of thoughts about earning money, due to stressful thinking about saving money.

Rumors say that Kahneman and Tversky did what they have always done, they submitted the paper to a psychological journal, but that it was rejected. They then opted to submit the paper to an economical journal. It was not only accepted. Because it was a journal read by economists, the theory spread like a wildfire among economists, making them abandon a utility-model that dated back to the renaissance.

And after Kahneman received the the Prize in Economics in memory of Alfred Nobel in 2002, because I knew something about psychology, I was offered the only fully funded PhD-position at a university-department for economic and business administration. The position included helping economic researchers, including professors, with methodological issues.

Framing (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981), e.g., how the manipulating of the way a situation is described will affect people's decision making.

Conjunction fallacy (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983) The delusion that several properties are more likely than one property.

Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

Representative bias (Kahneman & Tversky, 1972), e.g. the delusion that eating fat makes you fat. In reality, we really need to eat [animal] fat, e.g., for brain health (Ede, 2019).

Availability bias (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973), e.g., the delusion that information that is easy to imagine and that is repeated also is true. Example, when mainstream media reiterate that the world is warming rapidly. In reality, since the Eocene, the world is in a state of peak cold.

Simulation bias (Kahneman & Tversky, 1977), reminiscent of the above - that we use the first available mental representation as explanation, e.g. when thinking about domestic violence, assume that the typical perpetrator is a man. In reality, the typical perpetrator of domestic violence is a woman.

Prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), e.g., our species' inability to apply goal-oriented prospection, due to interruption of constructive memories. The typical example is the suppression of thoughts about earning money, due to stressful thinking about saving money.

Rumors say that Kahneman and Tversky did what they have always done, they submitted the paper to a psychological journal, but that it was rejected. They then opted to submit the paper to an economical journal. It was not only accepted. Because it was a journal read by economists, the theory spread like a wildfire among economists, making them abandon a utility-model that dated back to the renaissance.

And after Kahneman received the the Prize in Economics in memory of Alfred Nobel in 2002, because I knew something about psychology, I was offered the only fully funded PhD-position at a university-department for economic and business administration. The position included helping economic researchers, including professors, with methodological issues.

Framing (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981), e.g., how the manipulating of the way a situation is described will affect people's decision making.

Conjunction fallacy (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983) The delusion that several properties are more likely than one property.

Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

More about my expertise:

Executive coaching for CEOs/managers and workshops to facilitate Organizational Performance, Learning, and Creativity for Problem Solving | Lectures: Nutrition for physical and mental health | Course/lecture: children's emotional and social adjustment and cognitive development | Language training - Swedish | Academy Competency | CV | Teaching skills and experience | Summary of research project | Instagram | Linkedin | YouTube-channel | TikTok | Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment