Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

On September 4th 2019, the result of a HELSUS-survey, done at Vik campus at the University of Helsingfors, was posted on the university blog.In that post, they claimed:

“In relation to FOOD, many suggested choosing vegetarian or vegan options during lunch and having them as the preferred catering option in meetings and seminars”.The aim of the survey was to project future diet options to improve sustainability in the workplace.

Link to source.

Does that include well-being?

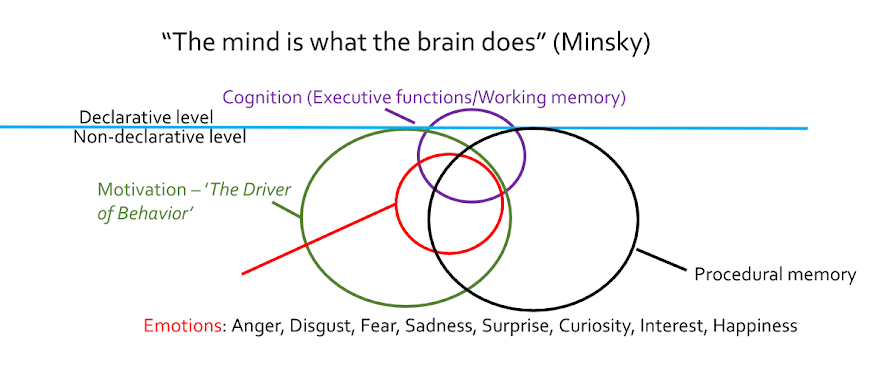

I'm a psychological scientist specializing in executive functions and prospective thinking, e.g. leadership, decision making, work climate, organizational learning, entrepreneurial thinking, and social creativity for problem solving and innovation, as well as nutrition psychology.

In August 2018, I was recruited as a research leader at the University of Helsingfors to investigate the future of food production from a perspective of entrepreneurial thinking.

Because of my expertise in psychology, I was also assigned to be the head of the department's well being team. (Metnal health issues was soaring the the University. Some say that the prevalence was ~20%).

When I teach method, I typically talk about representativeness, validity, and reliability.

There are difference ways of conducting studies, about because of that, reliability and validity vary.

The Gold-standard in research is experiment studies or Randomized control trials (RCT).

If you use questionnaires, make sure to avoid asking people to remember or to predict the future. Latent construct should also be used.

When sampling data, more than 30 people or less than 5% of the population should be included.

The method used was an inquiry with direct options in the format ‘willingness to …’.

The response rate was 1,8%.

Another aspect is conceptual stuff about nutrition and sustainability.

Food goes deep with people – it is the glue that holds sociocultural systems together. For example, during Christmas, we eat certain foods. Not because it relates only to Christianity, but because it relates to the systemic transformation and merging between Christianity, Nordic mythology, and enlightenment thinking that has been taking place since the start of the current era.

Our mind has the capacity for epistemic and instrumental rational thinking (Stanovich, 2011, 2016). That means that we can comprehend that food has been with us longer than that.

The so-called human lineage goes back some 7 – 6 million years before the present. One theory suggests Tugen Hills, a lush mountain area located between Lake Victoria in Uganda, which is the source of the river Nile, and Lake Turkana mostly located in Kenya; the northern tip of Lake Turkana is located in Ethiopia. There lived Orrorin man, who ate vegetarian options and likely had a brain size like a modern ape 300 – 350 cc (Pickford, 2006).

Ethiopia is where they found ‘Lucy’ (Australopithecus afarensis (3.9 – 3.9 Mya) Their brain size (~450 cc) exceeded Orrorin man's by ~40% (Johanson and Gray, 1974).

Findings suggests that ~300 000 years into their existence, Lucy’s kind changed their diet. From relying on a plant-based diet they added animal fats – bone marrow. In the search for the super-nutritious bone marrow, “Lucy’s kind” had to smash stones onto the bones of big dead animals. This 'percussive' behavior changed the form of their hands, and the change of diet initiated a reduction of their guts and an expansion of their brains (Aiello and Wheeler, 1995; Mann, 2018; McPherron et al. 2010; Pontzer et al. 2016; Thompson et al. 2019).

~800 000 years later, our genus, Homo, existed, with a brain size >90% larger than Orrorin man's, and ~40% larger than Lucy's (Kimbel och Villmoare, 2016; Villmoare, 2018; Villmoare et al. 2015).

Soon after (2.58 Mya), a significant climate change, from Pliocene to Pleistocene, occurred (Cohen et al.).

Sometime around this time, its known they ate meat (Gibbons, 2018; Pobiner, 2013; Zaraska, 2016).

On the shores of Lake Turkana, paleo anthropologists found the remains of Nariokotome boy (Homo ergaster/Erectus), capable of long distance running. Brain size ~900 cc, or ~44% larger than Homo Habilis (Brown, Harris, Leakey and Walker, 1985).

~320 000 years before the present, our specific species – Homo Sapiens – existed (Hublin et al. 2017).

The expansion of their brains eventually gave room for new mental faculties – social cognition, symbolic thinking, executive functions, and language (Ambrose, 2010; Coolidge and Wynn, 2018; Pagel, 2017, 2019; Pringle, 2016). This include the ability to elaborate intentions and scenarios and run them forward time (Gilbert and Wilson, 2007; Kaku, 2014).

At the ending of Pleistocene, during a period called the Epipaleolithic, when the ice melted at rapid speed due to several melt pulses, some of them settled (Hodder, 2018).

With these extended mental abilities, they opted to bake the first known bread some 14 000 years ago (Arranz-Otaegui et al. 2018), and ~1500 years later, they brewed first known beer (Liu et al., 2018). And despite the lack of nutrients, and for being very time-consuming to produce, this plant-based diet was cherished (used for ‘special’ occasions).

But this change of lifestyle, from fats- and meat consuming hunting and gathering to plant-based eating settlers, took its toll on health, transformed societies from egalitarian to hierarchical (Kohler et al. 2017; Mummert et al. 2011).

Still, the modern human brain needs animal fats to function (Ede, 2019; Mayo clinic, 2016).

Men over 40 who abstain from meat and eggs, both rich in choline, had an increased risk of suffering from dementia (Ylilauri et al (2019). Note. Finland is topping the global Alzheimer's ranking.

Production of animal source food in the western hemisphere, has little to no impact on the climate (White and Hall (2017). That is due to the Biogenic Carbon Cycle.

Despite capacities such as executive functions, prospection, and epistemic and instrumental rational thinking, when the future is uncertain (lack of prospective intentions), we tend to worry about the future. perhaps about the climate? Worrying about the future, neuroticism, as well as anxiety and depression, are associated (correlated) with a lack of food of animal origin.

Worrying about the future, neuroticism, as well as anxiety and depression, is associated (correlated) with abstinence from eating animal source food (Forestell and Nezlek, 2018; Nezlek, Forestell and Newman, 2018).

When the brain and the mind don't operate properly, we have an increased risk of falling in various mental fallacies. There are >200 mental fallacies, e.g. confirmation bias Wason, that we apply the same theory on everything, or search for information which supports our believes1960, 1966; 1968; Wason och Shapiro, 1971), “natural stupidity” – our species propensity to rely on information which are either prototypical (Kahneman och Tversky, 1972), available (Tversky och Kahneman, 1973), or just easy to access (Kahneman and Tversky, 1977), and dysrationalia – the inability to think and behave rationally despite adequate intelligence (Stanovich, 2009).

The HELSUS-survey is part of a larger context: “C You in Vik–initiative“ established earlier this year as a joint effort of nine enthusiastic persons working and studying in the campus”, based on the question:

“How do we make environmentally ‘smart’ practices visible and embed them into our actions at work?”Long story short. The students’ inspiration for this project originates at the University of Helsingfors new Responsibility and Sustainability program which contains several subcategories: (1) research, teaching, and partnership. (2) campus, (3) financial, (4) cultural, and (5) social. Even so, the key concept is sustainable development.

According to Wikipedia, the English version, Sustainable development originates from the Brundtland report, and can be defined as

“development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations”.Sustainability, the first part of the concept ‘Sustainable development’, refers generally to the capacity for the biosphere and human civilization to coexist, and It’s about systems thinking, which means there are multiple factors at play in the model.

Systems thinking resonates with the movements like ‘the Learning Organization’, coined by famous MIT-professor, Dr. Peter Senge. In 1998, Senge defined a learning organization as:

“a group of people working together to collectively enhance their capacities to create results that they truly care about” (Fulmer and Keys, 1998, p. 35).Learning is cognitive and social and comes in yet a variety of fashions, including adaptive, meaning coping with existing procedures and culture. Generative learning could, from a conceptual point of view, be seen as a mix of the cognitive blending we call creativity, and explorative thinking/disjunctive reasoning that considers all options (Nickerson, 1998; Stanovich, 2009).

For example, learning the Pythagorean axiom is considered adaptive, because it has already been invented. But Pythagoras (570 – 495 BC) himself used generative learning, that is, explorative thinking and creativity to come up with the infamous formula that describes how to calculate the diagonal of a square by taking the square root of the sums of the squared sides. (Did I get it right, or am I square?)

Another great leap was made by Filippo Brunelleschi’s (1377 – 1446) feat by erecting the dome for the roofless Cathedral of Florence. Brunelleschi’s work is said to have kick-started the renaissance – the rebirth of the rational and explorative thinking applied by people like Pythagoras, that had been suppressed by honor cultures since ~475 AD.

Explorative thinking and creativity were also used by people like (1) Darwin (1809 – 1882) and Wallas (1823 – 1913), when they jointly presented the theory of evolution by natural [and sexual] selection 1859, (2), and Marie Curie (1867 – 1934) in her pioneering research on radioactivity.

In parallel with this reborn zeitgeist for explorative thinking, which has led humanity to the global progress most of us can enjoy (Pinker, 2011, 2018), Emanuel Swedenborg (1688 – 1772), Sweden's most renowned scientist at the time, had caught an interest in mysticism. Swedenborg, enrolled at the Uppsala university at the age of 11 (1699). His studies continued until 1709. Thereafter, he traveled around Europe to further his education. In 1724, he was offered a professorship in mathematics, which he declined. In 1734, Swedenborg published his treatise Opera philosophica et mineralis, which included the chapter Principia Rerum Naturalium. About ten years later, he began to take an interest in mysticism. In 1758, Swedenborg published Heaven and Hell. It can be assumed that Swedenborg's interests created a so-called zeitgeist.

Eventually, the New Church was founded in his name, and followed his claimed revelations – a deeper understanding about how people should prepare for the second coming of Jesus:

“Drawing on the passage in Genesis (1:29-31) in which God Institute a vegan diet, Swedenborg said that meat-eating corresponds to the fall from grace in the Garden of Eden and was, therefore, the point of entry of sin and suffering into the world” (Phelps, p. 149).In 1817 the Swedenborgian Church of North America was established:

“and 1845, when the movement toward Swedenborg was in full tide, George Bush, professor of Hebrew and Oriental Literature in the University of the City of New York and long a favorite oracle of the orthodox church, was converted and took the lead of it” (John Humphrey Noyes (1811 – 1886), Letters: 1867).In parallel to that, the Temperance societies emerged inspired by John Edgar, professor of theology, and Presbyterian Church of Ireland minister. Sylvester Graham (Graham Crackers; 1794 – 1851) joined the Temperance movement in 1830 for a few months but then left to focus on promoting a plant-based 'Garden-of-Eden' diet. In 1850 Graham, together with Alcott, William Metcalfe (1788 – 1862), and Russell Trall, founded the American Vegetarian Society

“The meeting was called by William Metcalfe who had led a migration of 40 members of the Bible Christian Church from England to Philadelphia in 1817, all abstainers from flesh foods. By 1830 Sylvester Graham (picture right) and William Alcott MD were also following the meatless diet. Metcalfe soon heard about the formation of the Vegetarian Society in Britain in 1847, and about the new word 'Vegetarian' now being used. He contacted Graham and Alcott and arranged the New York gathering” (IVU).In 1830, William Millet (1782 – 1849) is said to have started an Adventist movement with a similar ambition, that is, also projecting the second coming of Jesus. And Millet had a date: October 22, 1844. The failure of the prophecy led to the Great Disappointment and the formation of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church (SDAC). Millet's goal-statement was reframed to a starting point.

Seventh Day Adventist Church (SDAC) was formally established in 1863, following the religious zeitgeist to promote a Garden-Eden, plant-based, diet in preparation for the second coming of Jesus.

One of the prominent members of SDAC was a young teenage girl named Ellen G. White (1827 – 1915). She claimed that meat, milk, and butter were responsible for 'carnal urges' – impure thoughts in men. Another early member, John Harvey Kellogg (1852 – 1943), developed breakfast cereals as a 'healthy food' (Figure 3). We know the brand because his brother William founded Kellogg's (Wikipedia).

|

Figure 3. Seventh-Day Adventist church transformed into Loma Linda promoting a 'balanced diet'. The current ad dates 1969. |

Malmros' work was noticed by another epidemiologist – Ancel Keys (1904 – 2004). Keys gathered data from 22 countries to test the diet-heart hypothesis, but he failed to find any correlations. Instead of admitting the obvious, Key's began removing countries. The Seven countries study was born. One of the countries was Finland, with samples från Åbo in west and North Karelia in the northeast (Teicholz, 2014).

In parallel John Yudkin (1910 – 1995), a Russian-Britsh physiologist was one of the first to claim a causal relationship between consumption of sugar and other refined carbohydrates, and heart disease; Yudkin also showed that sugar caused metabolic syndrome, which manifests in obesity and type-2 diabetes (Yudkin, 1972/1986/2012).

But because Ancel Keys (1904 – 2014), the founder of Seven Countries study, got more attention, most of us have been cultivated to believe that these diseases are explained by consumption of saturated fats, things containing cholesterol, and red meat, the so-called diet-heart hypothesis (Leslie, 2016; Taubes, 2001; Teicholz, 2014).

Why did we get it so wrong?

The explanation lies on our human mind, which easily falls victim of the mental fallacies, e.g. confirmation bias Wason, that we apply the same theory on everything, or search for information which supports our believes1960, 1966; 1968; Wason och Shapiro, 1971), “natural stupidity” – our species propensity to rely on information which are either prototypical (Kahneman och Tversky, 1972), available (Tversky och Kahneman, 1973), or just easy to access (Kahneman and Tversky, 1977), and dysrationalia – the inability to think and behave rationally despite adequate intelligence (Stanovich, 2009).

And with the latest IPCC report, the media took the chance to claim that the committee had given guidelines on diet (we must stop eating meat – for the climate).

As this was false, IPCC took to Twitter to reject that, but as always, it was too late. Soon after, a university in London banned the serving of meat in the cafeteria, and soon after that, the University of Cambridge followed suit.

Current research rejects:

- any association between saturated fats and cardiovascular disease (CVD; Howard et al. 2006; Ramsden et al., 2016). Replacing saturated fats with carbohydrates will increase health risks, including CVD (Dehghan et al 2017).

- any claim about a significant influence from production of meat and dairy on the climate. In reality, emissions from agriculture make out a small portion of the emissions (White and Hall, 2017).

The sad story though, we eat more processed food than ever, which should be considered the real issue (Hall et al 2019).

In the HELSUS survey, 6 respondents claimed they would be ‘willing to’ change to a vegan alternative to real food. That’s 17 % of the respondents. Generalizing the result on the population, the 1900 people working at Vik Campus, suggest 323 people are elaborating on doing that switch. Really?

ICAN, a survey performed by AS Nielsen, famous for doing consumer analysis on a global scale, shows that over a long period of time, 95 % of the population choose food based on taste and prize. 4 % ask for local and/or organic. 1 % demand things like the vegan alternative.

How can the willingness to abandon real food be 17 times higher at Vik Campus compared to the general population?

Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

More about my expertise:

Executive coaching for CEOs/managers and workshops to facilitate Organizational Performance, Learning, and Creativity for Problem Solving | Lectures: Nutrition for physical and mental health | Course/lecture: children's emotional and social adjustment and cognitive development | Language training - Swedish | Academy Competency | CV | Teaching skills and experience | Summary of research project | Instagram| Linkedin | YouTube-channel | TikTok | Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment