Peter Österberg

Department of Psychology, Lund University

The article has been updated - the content is the same, but the order has changed.

Abstract The purpose of this paper is to investigate emotions in thMcCle context of social and organizational creativity. The conclusions made from this paper are that emotions play crucial roles in learning and idea generation as well as for decision making; emotions can be interpreted by others as well as triggered by leaders. An emergent thought that came during the process of writing this paper was the two-factor approach common to many models of psychology (in leadership, decision making, cognition, and so forth). Most models concerning human behavior seem to involve things that can be verbalized and things that cannot; conscious and unconscious thoughts seem to be present at every aspect of human thinking. In Locke and Latham’s Goal-setting theory challenging symbolic representation, either by imagery or by leadership assignment, triggers motivation which in turn explains the behavior. The challenge triggers an impulse to explore. I try to address this in my dual role model for leadership - Generative learning management (Österberg, 2004).

Keywords: Leadership, organization, motivation, emotion, social creativity. 10 pages.

Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

Österberg (2004) proposed a dual-role model where leaders should combine the assignment of goals with the decentralization of decision making concerning developing strategies to attain the goals to the level of operations in order to influence social creativity within an organization.

Goal-setting is the ability to elaborate scenarios and intentions forward in time (Atance and O'Neill, 2001, 2005; Barkley et al. 2001; Gilbert och Wilson, 2007; Locke and Latham, 2002; Tomasello et al. 2005). Locke, Shaw, Saari & Latham (1981).

Creativity is here defined as the process of combining unrelated knowledge objects, or fragments of these objects, into new concepts. These concepts should be original and in some respect adaptable for a particular socio-cultural group (Simonton, 1999). This is illustrated by two examples.

First, testing scientific theories that others have presented cannot be considered original in a general sense, even though it can be original to some groups, and certainly adaptable.

Second, the inventions made during the ignition of the renaissance in Italy were both original and adaptable to people in Europe, even though these inventions most probably already had been made in China and were therefore no longer original to them (Menzies, 2008; Simonton, ibid.).

The processes of creativity are either intra- or interpersonal, but in both cases, creativity is taking place within a person’s brain & mind.

Further, research about organizational climate and creativity demonstrates an intervening role of work climate to the leader – performance relation (Ekvall och Ryhammar, 1998, 1999). Work climate leads thoughts to emotions.

How do emotions play into these interactions where social creativity is the outcome?

René Descartes (1596 — 1650) was a philosopher known for his mind-body dualism, is a philosophical concept that distinguishes between the mind and the body as two fundamentally different substances. Modern cognitive neuroscience has proven him wrong; to be able to make proper decisions and to act in a socially accepted way, thinking must be intertwined with emotional processing. Decision making, in general, constitutes the process of selecting and evaluating social and emotional information and this information must be relevant to a particular problem in order to generate possible solutions to that problem (Damasio, 2005; Gazzaniga, 2002).

Darwin (1872) stated the facial feedback hypothesis that suggests that emotions are expressed in a person's face. When we see people elevate the corner of their mouths (by activating a muscle called Zygomatic major), we interpret that they feel comforted and will act friendly. This effect also works in the opposite direction, through feedback. This means that when people elevate the corner of their mouths they will feel comforted to a greater extent compared to displaying a neutral facial expression. This is also true for frowning. When people lower the inside of their eyebrows (with a muscle called Corrugator supercilii), they experience discomfort (Österberg, 2001).

Facial expressions are displayed to inform people and other creatures in your environment of your current emotional state and also your intentions. Numerous examples are given about how salesmen, politicians, and news-readers consciously influence their counterparts by manipulating their facial expressions. Paul Ekman and his colleagues discovered that the expressions by themselves were sufficient to feedback significant changes in a person’s autonomic nervous system. This feedback phenomenon was tested in an experimental set up where respondents were asked to elevate the corners of their mouth when watching pictures of faces and neutral landscapes, and then what was thought to be the opposite: lowering their eyebrows in another round watching the same pictures. The result demonstrated a significant effect of facial expressions. This means that the respondents’ emotions changed by the way they consciously manipulated their facial muscles.

Emotion and facial expression are also related the opposite way; emotions cause involuntary facial expressions, like in the case of Mary the housewife whose attempt to commit suicide forced her to lie to the treating therapists, and they were all fooled by the lie (Ekman, 2001). The sessions with Mary was filmed for other purposes but when Ekman was told about her story he went back to analyze what had happened; in brief, he and his colleague Friesen identified what they called micro-expressions which are very hard-to-identify involuntary facial movements induced by emotions; Mary was weighted down by despair because she felt life no longer had any value, and this, according to Ekman, was briefly displayed in her face. So even though she verbally had lied about her intention for the therapist, her true emotions were revealed by her face.

Numerous taxonomies for emotions have been proposed, but no definite classification exists. Even so, love, joy, satisfaction, grief, jealousy, and anger, are six examples of general emotions (Gleitman et al., ibid., p. 470). At least six different facial affective expressions - happiness, fearfulness, disgust, sadness, anger, being surprised - are said to illustrate the basic emotions common to everyone in the world (Ekman and Friesen, 1975, in Buck, 1985).

Tomkins suggests that affect can be positive, negative, or neutral; surprise – startle does not come with either negative or positive value but will clear our mind from anything we were paying attention to at the moment. This emotional state may be the most interesting of them all and it seems to correspond to one part of the concept of goal setting, in the sense presented by Locke and Latham (ibid.).

James-Lange theory of emotion (developed by William James and Carl Lange in parallel) suggests that our subjective experience of emotion is a response to our own bodily changes (we feel afraid because we run). The theory was supported by some studies, but rejected by others. According to most contemporary researchers though, bodily reactions alone cannot account for emotional experience (Gleitman et al., 1999).

Schacter and Singer (1962) proposed a two-factor theory (attribution of arousal theory or cognitive arousal theory) suggesting both physiological as well as cognitive influences to determine the emotional experience. Example: When a person runs into a barking dog, his or her reaction will probably be determined by the cognitive interpretation of that meeting (some cognition is suggested to take place, even though on an implicit level, in combination with direct physiological reactions). In our daily life, we may wake up from a dream with a smile on our face or shivering in a cold sweat from a nightmare. In a similar way, entering your manager’s office may cause your palms to sweat and your stomach may feel out of control. This physical reaction may also occur when you meet someone you feel physically attracted to. In either case, our heart will pound which is an emotional reaction. Decision making - the process of selecting and evaluating social and emotional information (Gazzaniga et al., ibid.) – then works to interpret the situation. These processes occur in parallel, meaning that you can't put one before the other.

Motivation is a superordinate concept which explain human behavior: performance, knowledge acquisition, as well as the ability to elaborate scenarios and intentions forward in time (Locke, Shaw, Saari & Latham (1981):

“Goals affect performance by directing attention, mobilizing effort, increasing persistence, and motivating strategy development. Goal setting is most likely to improve task performance when the goals are specific and sufficiently challenging”.Buck (1985) proposed a meta-theory about emotion, based on three theoretical proposals starting with “prime” (primary motivational/emotional systems which are biologically based on an active inner process that requires external stimuli to reach expression. This theory spans from psychophysiology to cognition and has been suggested in a variety of theories proposed by Darwin, James-Lange, Schachter and Singer, Ekman, and Panksepp.

“It is not argued that any of these views are incorrect, rather that they are substantially correct as far as they go, but that they are incomplete and that it is possible to arrive at a comprehensive model of motivation and emotion by taking aspects of each of these views into account” (Buck, 1985, p, 390).PRIME:s are biological drives that work to energize behavior towards a fixed goal. The next level of affects in the motivational system are emotions: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust (in Buck, 1985, referring to Ekman and Friesen, 1975, and Tomkins, 1962/32; Panksepp, 2000).

Cacioppo and Berntson (1992):

“examines the importance of a multilevel, integrative approach to the study of mental and behavioral phenomena in the decade of the brain, reviews how this approach highlights the synergistic relationship between theoretical and clinically relevant research, and illustrates how this approach can foster the transition from microtheories to general psychological theories”.According to Martindale (1999), a low level of emotional arousal (which is opposite to emotional tension) is associated with the ability to solve complex tasks where creativity and learning new things is demanded; high arousal levels provide an appropriate climate for simple tasks where familiar strategies will be applied.

Emotions are implicit which means they work in the background and are very hard to control directly. The parts of the brain which handle emotions evolved long before the areas for consciousness and cognition (Gazzaniga, 2002).

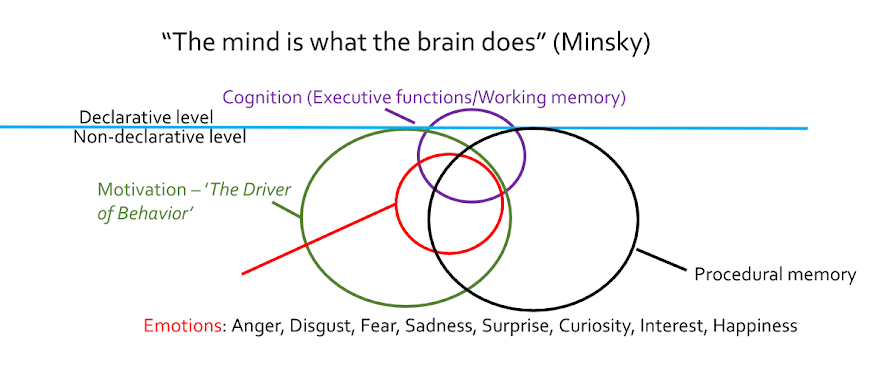

Flaherty (2005) suggests a three-factor anatomical model for idea generation (and creative drive); parts of the neocortical structures like the temporal and frontal lobe are suggested to interact in this process with parts of the “older” (limbic) brain which holds responsibility for human emotions as well as motivational drive. This approach, that declarative or explicit memory instances co-operate, is common in theories associated with cognition, emotion, and motivation as well as in neuroscience.

Goleman (2006) suggests that with high emotional tension, the pathways to the hippocampi – the brain's central units for administrating rational thinking and learning (there's one in each hemisphere) – are blocked, leaving us with the simple alternatives of fight or flight.

Bechara and Bar-on (2006) argue that emotional intelligence – the multi-factorial array of interrelated emotional, personal, and social competencies that influence our ability to cope actively and effectively with daily demands – is closely related with Thorndike’s definition of social intelligence – the ability to perceive one’s own and other’s internal states, motives, and behaviors, and to act toward them optimally on the basis of that information. They further argue for the empirical evidence that discriminates emotional and social intelligence from “cold” cognition, which means humans can't be just rational; emotions are always involved. This means that inter-personal exchange processes, in complex problem solving, for example, demands more than just cognitive ability.

Our “emotional intelligence” helps us to understand who we are and how we interact with our environment. Emotions are what the outside observer can see or measure, whereas feelings are what the individual senses or experiences subjectively (Bechara and Bar-On, ibid.). This perspective goes back to Darwin who determined that humans have evolved a finite set of basic emotional states, each of which is unique in its adaptive significance and physiological expression. The proposals made by Darwin are that:

- Emotion is based on activity in neurochemical systems in the central nervous system

- these systems are the product of evolution and reflect survival requirements within each species

- activity in these systems can be modified by learning (as referred to by Buck, 1985, p. 389).

Our emotional personality seems to be situated in the prefrontal cortex; studies of monkeys where this area had been dislocated showed no emotional life. The monkeys became crippled in a social sense, even losing their sexual ability, and were finally pushed away by the other monkeys in the group to die in loneliness. The same holds for humans. Emotional expressions that are typical for a person are correlated with the prefrontal cortex or at least parts of it. In the cases of Phineas Gage and Elliot (for reading in-depth, please consult Antonio Damasio’s Descartes error), both persons lost their “personality” (or emotional self) as the lower or upper region of the prefrontal cortex was damaged. They both seemed to keep their intelligence intact, but lost personality traits associated with an emotional self; they also lacked the ability to be creative. Lacking the ability to sense or imagine emotional risk is devastating in decision making, reason, and rational thinking, which are controlled by somatic markers – the emotional association in cognitive processing which causes affective displays; for example “gut feeling” Emotions are the key to most of the intra- and interpersonal activities people engage in; what happens inside of us influences what happens when we encounter subjects and objects in our environment:

“Pure rational thinking without any emotional or social support leads to bad adjustment. Sometimes to catastrophe ((Eriksson, 2001), p. 34).The impact of emotions has been popularized in Malcolm Gladwell (2005) in Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, and Jonah Lehrer (2009) in The Decisive Moment: How the Brain Makes Up Its Mind. The latter also reviewed by (Holland, 2010).

Lehrer points at two central anatomical areas in the brain to be responsible for decision making and corrections when your decisions are wrong. These are called the Orbitofrontal cortex (Kringelbach, 2005) and Anterior cingulate cortex (Pardo, Pardo, Janer & Raichle, 1990). Even though many different areas in the brain are involved in decision making, the orbitofrontal cortex seems to be particularly important.

Emotions as tools for Leaders

There are several models in the framework of leadership – organizational behavior that emphasizes the importance for leaders to use a combination of roles to direct peoples’ attention as well as igniting individual qualities that will impact on the processes of solving the complex problem (Yukl, 2006). A leader can influence human performance, [generative] learning, and creative problem solving by his or her verbal communication - assigning goals (Locke and Latham, 2002; Locke, Shaw, Saari & Latham, 1981). Some emotional related variables play a mediating or intervening role in the relationship between leadership and organizational behavior:

- Challenge. Emotions are also dependent on goals and actions. For goal setting to be effective, a challenge must be a part of the concept (Locke, Shaw, Saari & Latham (1981). This is manifested in the original intention of brainstorming: to ignite motivation to be creative by assigning a challenging goal (Litchfield (2008). Challenges can come out of the blue as well, like in a crisis situation. Suddenly, control is lost and there is a demand for hasty and brave decisions. These are situations when knowledge about how to solve a problem is absent - when creativity is called upon. These types of problems are referred to as complex (Duncker, 1945; Wood & Locke, 1990).

One famous example of complex problem solving was the invention of a carbon dioxide filter to the space shuttle of the Apollo 13 expedition 1970. (In the movie, one of the leaders holds up two artifacts, a cylinder and a cube in front of the group assigned to solve the problem, stating: The mission can be described as “to put this into that”, referring to the process of adding two disparate objects into one another.). -

Decentralization. This process is facilitated when decisions about strategies are decentralized to the level of operations (Lord and Maher, 1991; McClelland and Rumelhart, 1985

“The model consists of a large number of simple processing elements which send excitatory and inhibitory signals to each other via modifiable connections. Information processing is thought of as the process whereby patterns of activation are formed over the units in the model through their excitatory and inhibitory interactions” (p. 159).

A consequence of decentralization can be an increase in Self-efficacy – the perception of one’s own work competence (Bandura, 1977; Locke and Latham, 2002). People who “sense” they have a good work competence will show better work performance compared to people who lack self-efficacy; when leaders assign challenging goals to a subordinate or the whole organization for that matter, the receiver of the message gets the impression that the leader believes that the receiver has the ability to perform. -

Deferment of judgement. The Osborne - Parnes approach to creativity (popularized through the brainstorming concept) emphasizes another important factor that may affect emotional tension among a problem-solving group: deferment of judgment. In this process, a person is assigned to facilitate the process - to keep up a good mood among the participants and to help them focus on idea generation. The purpose of deferment of judgment is to establish a positive climate where people feel safe to sustain an open mind for idea generation (Basadur, 2004). In general, it seems to be implicit factors like motivation and emotion that facilitate creative performance in a group or organization. People who are emotionally relaxed by the influence of work climate, and highly motivated by goal assignment will have no problem trying to think outside the box when demands are high.

- Surprise is another emotional trigger. (Fenker & Schütze, 2008) showed how surprise triggered a cyclic or interactive release of dopamine between the hippocampus and the substantia nigra> (SN) and ventral tegmental area (VTA).

- Trust – the psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another - is one such example (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt & Camerer, 1998). From a creative point of view, trust in the leader plays an important role for people who tend to give suggestions that may be “outside the box.” Rousseau et al. (ibid) argue for a path-dependency between trust and risk; “risk creates an opportunity for trust, which leads to risk-taking” (p. 395).

- Work climate. The ten-dimensional scale called Creative Climate Questionnaire (CCQ; Ekvall, 1996) works in a similar way. The assessment includes factors that are associated with playfulness, leader’s openness towards debate, idea time, and trust. The concept varies between disciplines, and Isaksen and Ekvall (2006) associate trust with openness and defines these two merged concepts as the emotional safety in relationships displayed in an organization (with this definition, trust and openness is a part of the American version of Creative climate Questionnaire called Situational Outlook Questionnaire). Ekvall och Ryhammar (1998, 1999) demonstrated that leaders may influence the creative outcome by working to improve the work climate, that is, lower the emotional tension among employees, which could be interpreted as providing for relaxed and positive emotions within the organization.

Conclusions.The conclusions made from this paper are that emotions play crucial roles in learning and idea generation as well as for decision making; emotions can be interpreted by others as well as triggered by leaders. An emergent thought that came during the process of writing this paper was the two-factor approach common to many models of psychology (in leadership, decision making, cognition, and so forth). Most models concerning human behavior seem to involve things that can be verbalized and things that cannot; conscious and unconscious thoughts seem to be present at every aspect of human thinking. In Locke and Latham’s Goal-setting theory (2002) challenging symbolic representation, either by imagery or by leadership assignment, triggers motivation which in turn explains the behavior. The challenge triggers an impulse to explore. I try to address this in my dual role model for leadership - Generative learning management (Österberg, 2004).

Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

Mer om min expertis:

Executive coaching for CEOs/managers and workshops to facilitate Organizational Performance, Learning, and Creativity for Problem Solving | Lectures: Nutrition for physical and mental health | Course/lecture: children's emotional and social adjustment and cognitive development | Language training - Swedish | Academy Competency | CV | Teaching skills and experience | Summary of research project | Instagram | Linkedin | YouTube-channel | TikTok | Twitter

References

Atance, C.M., and ONeill, D.K. (2001) Episodic future thinking. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, (12), 533-539.Atance, C.M. and ONeill, D.K. (2005). The emergence of episodic future thinking in humans. Learning and Motivation, (36), 126-144.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review, 84 (2), 191-215.

Barkley, R. A. (2001). The executive functions and self-regulation: An evolutionary neuropsychological perspective. Neuropsychology Review, 11(1), 1–29.

Basadur, M. (2004). Leading others to think innovatively together: Creative leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 15, 103–121.

Buck, R. (1985). Prime Theory: An Integrated View of Motivation and Emotion. Psychological Review, 92(3), 389-413.

Bechara, A. & Bar-On, R. (2006). Emotional Substrates of Emotional and Social Intelligence: Evidence from Patients with Focal Brain Lesions. In J.T. Cacioppo, P.S. Visser., C.L. Pickett (eds.) Social Neuroscience – people thinking about thinking of people. MIT Press, Massachusetts.

Cacioppo, J.T. & Berntson, G.G. (1992). Social Psychological Contributions to the Decade of the Brain: Doctrine of Multilevel Analysis. American Psychologist, 47 (8). 1019-1028.

Carrere, S. & Gottman, J.M. (1999).Predicting divorce among newlyweds from the first three minutes of a marital conflict discussion. Family Process, 38, 293-301.

Damasio, A. (2005). Descartes’ error: emotion, reason, and the human brain. Penguin Group, New York.

Duncker, K. (1945). On Problem Solving. Psychological Monographs, 58(270), 1-113.

Ekman, P. (2001). Telling lies - Clues to deceit in the marketplace, politics, and marriage. Norton & Company, New York.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1975). Unmasking the face: A guide to recognizing emotions from facial clues. Prentice-Hall.

Ekvall, G. (1996). Organizational Climate for Creativity and Innovation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. Vol 5(1), 105-123.

Ekvall, G., Ryhammar, L. (1998). Leadership style, Social Climate, and Organizational outcomes: A study of a Swedish University College. Creativity and Innovation Management, 7(3), 126-130.

Ekvall, G., & Ryhammar, L. (1999). The creative climate: Its determinants and effects at a Swedish university. Creativity Research Journal, 12(4), 303–310.

Eriksson, H. (2001). Neuropsykologi: Normalfunktion, demenser och avgränsade hjärnfunktioner. Liber, Stockholm.

Fenker, D., Schütze, H. (2008). Learning by Surprise. Scientific American: Mind, 19 (6), 47.

Finke, R.A. (1996). Imagery, Creativity, and Emergent Structure. Consciousness and Cognition, 5, 381–393.

Finke, R.A., Ward, T.M.& Smith, S.M. (1992). Creative Cognition: Theory, Research, and Application. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Flaherty, A.W. (2005). Frontotemporal and Domanineric Control of Idea Generation and Creative Drive. The Journal of Contemporary Neurobiology, 493, 147 – 153.

Gazzaniga, M.S., Ivry, R.B., Mangun, G.R. (2002). Cognitive Neuroscience: The Biology of the mind. New York and London: Norton & Company.

Gilbert, D.T. & Wilson, T.D. (2007). Prospection: Experiencing the future. Science, 317 (5843), 1351–1354.

Gladwell, M. (2005). Blink – The Power of Thinking without Thinking. Penguin Book, New York.

Gleitman, H., Fridlund, A.J., and Reisberg, D. (1999). Psychology. New York and London: Norton & Company.

Goleman, D. (2006). Social intelligence: The new science of human relationships. London, Arrow books.

Holland, J. (2010). The Decisive Moment: How the Brain Makes Up its Mind by Jonah Lehrer. Jessica Holland finds food for thought in this entertaining dissection of our grey matter. The Guardian.

Isaksen, S.G. & Ekvall, G. (2006). Assessing Your Context for Change: A Technical Manual for the Situational Outlook Questionnaire. New York, the Creative Problem Solving Group Inc.

Kringelbach, M.L. (2005). The human orbitofrontal cortex: linking reward to hedonic experience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6, 691–702.

Lehrer, J. (2009). The Decisive Moment: How the Brain Makes Up Its Mind. Text Publishing; Export and airside ed edition.

Litchfield, R. C. (2008). Brainstorming reconsidered: A goal-based view. Academy of Management Review, 33(3), 649-668.

Locke, E. and Latham, G (2002). Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation. American Psychologist, Vol. 57, No. 9, 705–717.

Martindale, C. (1999). Biological bases of Creativity. In: R.J. Sternberg's. (ed) Handbook of Creativity, pp. 137 – 152. New York, Cambridge University Press.

Menzies, G. (2008). 1434 - The year a Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance. HarperCollins, London.

Österberg, P. (2001). Facial feedback: Hur man med ett leende kan tolka omvärlden mer positivt. Unpublished bachelor thesis. Department of Psychology, Uppsala University.

Österberg, P. (2004). Generative learning management: A hypothetical model. The learning organization, 11(2), 145-157.

Panksepp J. (2000). Affective consciousness and the instinctual motor system: the neural sources of sadness and joy. In: Ellis R, Newton N, eds. The Caldron of Consciousness: Motivation, Affect and Self-organization, Advances in Consciousness Research. pp. 27-54, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. & Co.

Pardo, J.V., Pardo, P.J., Janer, K.W. & Raichle, M.E. (1990). The anterior cingulate cortex mediates processing selection in the Stroop attentional conflict paradigm. PNAS, 87(1), 256–259.

Rousseau, D., Sitkin, S.B., Burt, R.S., and Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-Disciple View of Trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393 – 404.

Schachter, S., and Singer, J.E. (1962). Cognitive, Social, and Physiological Determinants of Emotional States. Psychological Review, 69 (5), 379-399.

Simonton, D., K. (1999). Origins of genius: Darwinian perspectives on creativity. London: Oxford University Press.

Tomasello M, Carpenter M, Call J, Behne T, Moll H. (2005) Understanding and sharing intentions: the origins of cultural coition. Behavior and Brain Sciences, 28 (5), 691-735.

Wood, R.E., & Locke, E.A. (1990). Goal setting and strategy effects on complex tasks. Research in organizational behavior, 12, 73 – 109.

Yukl, G. (2006). Leadership in organizations. (6th Ed.) New Jersey, Parson – Prentice Hall.

Terrific article! This is the type of info that should be shared across the web.

ReplyDeleteShame on Google for now not positioning this publish upper!

Come on over and visit my website . Thank you =)

Here is my web page :: job personality test