Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

Food producers (farmers) in the Netherlands are upset by politicians' decisions to halve the nitrogen output by 2030. For more than a week, food producers 'en masse' have protested against the decisions made by the politicians. The politicians response has been to send police to attack the food producers (Cagan, 2022, Bloomberg).

The politicians have also decided that the Netherlands should shift to something called circular economy by 2050.

In order for that to happen, the government of the Netherlands has presented three goals:

Link: Government of the Netherlands

The Kingdom of the Netherlands is situated by the North sea. With its 17 million people, Netherlands is one of the world's most densely populated countries with 400 - 500 people per square kilometer. To get a perspective, one can compare with Finland and Sweden; each of the countries has a population density of 16 and 23 people per square kilometer.

The Netherlands is known for food production, engineering, and trading. Rotterdam is the busiest sea port in the world.

it [Netherlands] is the world's second-largest exporter of food and agricultural products by value, owing to its fertile soil, mild climate, intensive agriculture, and inventiveness (Wikipedia).The Netherlands has a long tradition of ingenuity.

|

| Eduardo F. J. De Mulder; Ben C. De Pater; Joos C. Droogleever Fortuijn (28 July 2018). The Netherlands and the Dutch: A Physical and Human Geography, page 21. |

500 BC to 500 AD, they claimed land at a pace of 5-10 meters per year, which later, after precipitation had desalination, could be used for food production. In order for this to happen, they used their innate creative ability, and developed engineering know-how.

Creativity, the ability to meld non-related abstractions, and fragments thereof, into distinct categories, emerged some 70 000 years before the present. It's a predisposition of the human kind. It just needs to be ignited and facilitated in some way (Ambrose, 2010; Wynn, Coolidge and Bright, 2009; Österberg, 2012; Österberg and Köping Olsson, 2018, 2021).

Engineering, on the other hand, is a skill that needs to be learned and cultivated:

Link: Cambridge Dictionary

The people of the Netherlands kept using their ingenuity to reclaim more land. These skills developed over time, resulting in what Mulder et al. call the fourth kind of land reclamation:

The pressing question is: How big impact does Netherlands' food production have on the climate?

As shown in the diagram, The Netherlands has a similar CO2 profile as Finland and Sweden. Both Finland and Sweden are climate neutral when it comes to CO2-emissions. That's because both countries' share of CO2 makes out approximately 0.1 % of global ditto. That's also true for the Netherlands.

Another aspect of food production is the Biogenic Carbon cycle; methane from burping cows transforms into CO2 within 10-12 years by a process called hydroxyl oxidation. The same amount of CO2 is consumed by plants by a more familiar process - photosynthesis.

During spring 2019 Mats Nylund, chairman for Finland's Swedish speaking farm-cooperation wrote an op-ed in Hufvudsstadsbladet (Swedish). Nylund used official data from the Finnish central for statistics:

According to Statistics Finland, 74 per cent of all climate emissions in Finland come from the energy sector and the combustion of fossil fuels. Only 12 percent of the emissions come from agriculture. It is estimated that 56 per cent of agricultural emissions in Finland come from arable land and 44 per cent from livestock production according to Finland's medium-term climate policy plan. In plain language, this means that just under 5 per cent of Finland's climate emissions come from livestock production (HBL).This relation between emissions is similar across the western countries. White and Hall (2017) and Liebe, Hall and White (2020) have also dismissed the claim that livestock and dairy production produces significant amounts of green house gases.

But The Netherlands food producers did not react to decisions concerning CO2, but nitrogen, which is used in fertilizers. Our world in data showed that compared to Finland and Sweden, food producers in the Netherlands use more fertilizers:

The amount is approximately four times the amount used by food producers in Finland and Sweden. So the politicians may have a point.

In October 2018 I was invited by Finland's Swedish Agricultural Society's association (Svenska lantbrukssällskapens förbund) to give a lecture. They specifically asked for goal-setting. That makes sense because most people fail to apply goal setting in a proper way, yet it's the normal thinking of humans (Szpunar et al. 2014).

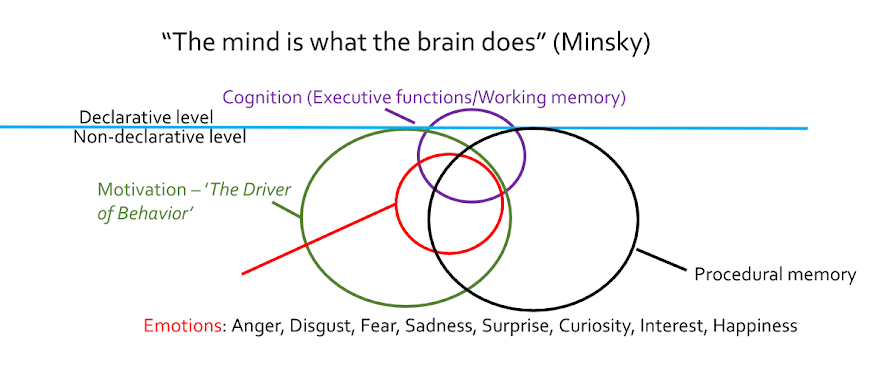

Goals influence motivation (Locke et al. 1981) which explains all kinds of behavior. Goals can be either abstract, clear or learning oriented. Psychological scientists have shown, using RCTs, that abstract goals have low efficacy, that there's a linear relation between clear goals and performance, and that learning goals - "the number of ideas or strategies one acquires or develops to accomplish the task effectively" - influence learning and exploratory thinking (Locke and Latham, 2002).

The Netherlands, which for centuries has proven to be a land of great ingenuity, is likely to have the brains to change the way the food is produced. But a dialogue between politicians and the food producers never occurred. Why?

Looking at the 2030/2050 statements, I suggest that the politicians of the Netherlands neither stated a clear nor a learning oriented goal to the farmers, but instead three abstract goals. These are proven not only to be associated with low efficacy, but also to create symbolic divergence. That means that people interpret the message in their own way, each of them convinced that their view is the correct one, and it may lead to conflicts.

Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

Mer om min expertis:

Executive coaching for CEOs/managers and workshops to facilitate Organizational Performance, Learning, and Creativity for Problem Solving | Lectures: Nutrition for physical and mental health | Course/lecture: children's emotional and social adjustment and cognitive development | Language training - Swedish | Academy Competency | CV | Teaching skills and experience | Summary of research project | Instagram | Linkedin | YouTube-channel | TikTok | Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment