Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

Geoffrey Hinton, a cognitive scientist/psychologist, and a “the Godfather of AI”, known for his work on artificial neural networks, reiterates this important message:

“When we remember, what we're doing is just making up a story that sounds plausible to us. That's what memories are” (Hinton, 2025).Philosophers and psychological scientists have investigated the human mind and its faculties, like memory. Because I'm not a philosopher but a psychological scientist, I consulted Chat Gtp with the following question: Which early philosophers investigated human mind and memory, and what did they come up with?

“The human mind and memory fascinated many early philosophers, particularly in Ancient Greece and later in the Roman world. Their insights, while not always scientific by modern standards, laid important conceptual foundations for psychology, epistemology, and metaphysics. Here's a concise overview of key early thinkers and their contributions:Even though our genus existed 2.8 million years before the present (Kimbel och Villmoare, 2016; Villmoare, 2018; Villmoare et al. 2015), our:

- Plato (427 – 347 BCE). Key works: Phaedrus, Theaetetus, Meno. Contributions: Memory as innate knowledge (anamnesis): Plato proposed that the soul is immortal and possesses all knowledge from previous incarnations. What we call "learning" is in fact recollection (anamnesis).

The tripartite soul: Reason (rational), spirit (emotional), and appetite (desires)—an early model of mental structure.

He used the metaphor of wax tablets to describe memory: impressions are stamped into the soul as onto soft wax.

- Aristotle (384–322 BCE). Key works: On the Soul (De Anima), On Memory and Recollection. Contributions: Memory as a passive faculty: Aristotle defined memory (mneme) as the retention of a sensory experience.

Recollection (anamnesis) is an active search process, involving association (e.g. similarity, contrast, contiguity).

Emphasized images (phantasmata) as the basis of thought—thinking is tied to imagination and sensory impressions.

Memory is grounded in time—we remember things as having happened in the past.

- Epicurus (341–270 BCE). Key ideas: Materialist psychology. Contributions: Memory results from the motion of atoms in the soul (made of fine particles).

All perception, thought, and memory are natural processes—there's no immortal soul. He believed impressions (eidola) from things in the world affect the mind, and memory stores these for future reference.

- Stoics (e.g. Zeno, Chrysippus). Timeframe: 3rd century BCE onward. Contributions: The soul is like a blank slate (tabula rasa) at birth, written on by experiences.

Memory and thought are impressions (phantasiai) that the rational soul accepts or rejects.

They emphasized mental discipline, self-reflection, and rational control over one's thoughts and impressions.

- Cicero (106–43 BCE). Key works: De Oratore, Tusculan Disputations. Contributions: In De Oratore, he discusses mnemonics (memory aids), attributing techniques like the method of loci (memory palace) to the poet Simonides. He saw memory as both natural and trainable, and essential for oratory and philosophy.

- Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE). Key work: Confessions (Book X). Contributions: One of the earliest introspective studies of memory.

He describes memory as a vast inner "storehouse"—a place within the soul where impressions, concepts, emotions, and even forgotten things reside.

Explores the relationship between memory, self, and God—anticipating existential and phenomenological questions”.

- specific species have existed 320 000 years before the present (Hublin et al. 2017),

- constructive memory probably emerged ~70 000 years before the present (Ambrose, 2010; Pringle, 2016; Schacter och Addis, 2007), as part of the executive functions (Adornetti, 2016; Ardila, 2008; Ardila et al. 2018; Barkley, 2001; Coolidge and Wynn, 2018).

And even though Elizabeht Ricord (1788 – 1865; 1839/1840) famously wrote that combinatory thinking is the highest level of thinking, Frederic Bartlett (1886 – 1969; 1932) may have been one of the first psychologists to warn us about trusting our memory.

Through my own research I have come to the following conclusions about memory:

- Memory is not for forming associations but for simulating intentions and scenarios about the future we don't know much about (Gilbert och Wilson, 2007; Gallister, 2017; Kaku, 2014).

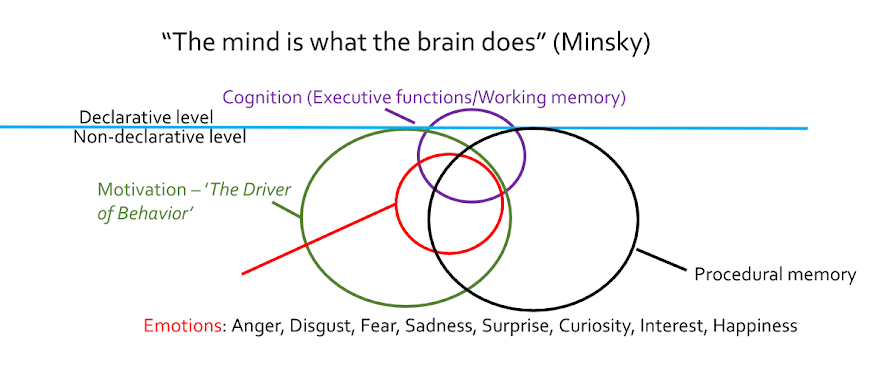

- Memory is divided into several instances: declarative and non-declarative respectively (Graf och Schacter, 1985; Squire och Zola, 1996).

- Declarative memory is divided into semantic, episodic and personal semantic (autobiographical).

- Semantic memory relates to facts – 2+2=4, Paris is the capital of France etc. and is stable over time (ScienceDirect).

-

Personal semantic knowledge, which include autobiographical knowledge and memories of repeated personal events (Renoult et al. 2016, p. 24; Renoult et al. 2012; the Memory Illusion; Szpunar et al. 2014).

- Autobiographical memory is formed around the age of 5-6 and is vulnerable to memory hacking (Fivush och Graci, 2017; Nelson och Fivush, 2004; Shaw, 2016).

- Episodic memory concerns events we have been part of. When we have to remember an event, a copy of the event is not retrieved from memory. Instead, a construction of the sequence of events takes place that is adapted to the current situation (Schacter och Addis, 2007), and is vulnerable to memory hacking (Shaw, 2016).

This can be illustrated by neurological correlates.

-

Semantic memories mainly activates the core region for (1) conceptual knowledge: Lateral temporal cortex (especially the anterior temporal lobe, ATL), (2) integrated knowledg: Inferior parietal lobule, (3) Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), which supports retrieval and selection of semantic information, and (4) Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC): when semantic knowledge has personal relevance or social meaning.

-

Personal semantic memories mainly activates (1) Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC): important for self-referential processing, (2) Lateral temporal cortex: supports fact-like representations, (3) Posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and precuneus: involved in personal perspective and self-related context, (4) Hippocampus: less involved than in episodic memory, but still contributes to contextual linkage

-

Autobiographical memories mainly activates by (1) Medial temporal lobe, especially the hippocampus: reconstructs episodic details, (2) Ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and mPFC: involved in personal relevance and integration, (3) Posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and precuneus: support imagery and perspective-taking, (4) Lateral temporal and parietal cortices: semantic scaffolding and scene construction, (5) Amygdala: involved when autobiographical memories are emotional.

- Episodic Memories (Memories of specific events, including what happened, where, and when — includes rich sensory and contextual detail) is mainly activated by (1) Hippocampus: crucial for binding “what–where–when” elements, (2) Entorhinal and perirhinal cortex: involved in encoding and retrieving item-context associations, (3) Posterior parietal cortex (including angular gyrus): supports attention to memory and vividness, (4), Prefrontal cortex (especially dorsolateral and ventrolateral): strategic retrieval and monitoring, (5) Precuneus and retrosplenial cortex: involved in scene construction and mental time travel.

Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

More about my expertise:

Executive coaching for CEOs/managers and workshops to facilitate Organizational Performance, Learning, and Creativity for Problem Solving | Lectures: Nutrition for physical and mental health | Course/lecture: children's emotional and social adjustment and cognitive development | Language training - Swedish | Academy Competency | CV | Teaching skills and experience | Summary of research project | Instagram | Linkedin | YouTube-channel | TikTok | X

No comments:

Post a Comment