Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

Approximately eleven thousand years ago, a climatic change opened a window of opportunity for the human race who due to its predisposition for adaptation and creativity based on evolution, settled down and developed agriculture and complex societies. Within 5,000 years this transformation spread from the land stretching from Palestine and lower Mesopotamia to the northeast corner of India and Britain in the west. This is a testimony to humans’ inborn openness to change, cognitive flexibility, and also their sensitivity to social impact (Cacciopo and Berntson, 1992; Cacciopo, Vicker and Pickett, 2006). In new complex societies, such as those of Sumer or Egypt, written language was invented and gave us the opportunity to transfer what we hear of something concrete (paper, papyrus, etc.). This occasionally made it possible to build an accounting system for trade and logistic operations. These new operations demanded technology, financial strength, and mental effort among other things, and some sort of social structure like an organized society was required. But societies and the organizations within them developed into large hierarchies. This meant putting one person at the top to rule, and having middle managers to execute the ruler’s decisions. To demonstrate the ruler’s divinity, and to sustain people’s compliance with this authority, King Aha in Egypt, ruler in the 30th century B.C., was among the first of many kings known today to be buried on a grand scale, taking with him a considerable number of subordinates to promote himself as being on top of everyone else. Similar burial rituals emerged in China and Mesopotamia some hundred years later and as late as the 16th century A.D. in Michoacán in western Mexico (Cook, 2003). Some 6 800 years after the introduction of Holocene, another step in human culture took place, Abraham migrated from Sumer (in Mesopotamia), a movement that later developed into the three predominant monotheistic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam). The key message of these religions was that humans had to abandon the belief that many different phenomena cooperate to explain everyday events, and to adopt a conception that one force was the cause of everything; things should not be explained from within or with a distributed perspective, but from the outside and above; learning and creativity were treated as something wrong. This is exemplified by the metaphoric account of Adam and Eve being driven from paradise after having been persuaded to eat the forbidden fruit representing knowledge (Jacobsen, 1976). Almost 5 000 years after the burial of King Aha, the industrial revolution began in Europe. Probably as a consequence of industrialism, Communism – an ideology that has proven to be one of the greatest obstacles to creativity and entrepreneurship – emerged through the Manifesto written mainly by Karl Marx in the mid-19th century. In practice, this ideology turned out to represent closed societies in which leaders took the role of dictators in order to control every aspect of human action in their society. Deportation of intellectuals and opponents to the Gulag were as common as the random killing of subordinates to demonstrate the contrast between rulers and subordinates, particularly in the former Soviet Union (Skott, 2001). Due to the industrial revolution, another level of complexity emerged that had not been encountered earlier; in the factory system, many people were assembled in the same production plant, and questions about how to manage large cohorts of people to sustain productivity had to be resolved. After thousands of years of practicing subordination to masters, the refinement of the application of hierarchies was close at hand. Management and efficiency became central themes in the young science of organization and management. Fredrick Taylor (1856-1915), one of the pioneers in this field, applied incentive systems to reinforce peoples’ work performance. Administrative and bureaucratic principles for organizational design emphasized rational thinking in a top-down perspective; top managers should do all the thinking, while workers were supposed to comply with given orders about strategy (Daft, 2006). Bureaucracy is now considered an inhibitor of creativity (Soriano de Alencar, 2012). Hierarchical systems remained as the primary source of organization design until the 1980ies, although the shift toward an enterprise culture resurrected during the 1970ies, including traits such as initiative, risk-taking, flexibility, creativity, independence, leadership, strong work ethic, daring spirit, and responsibility (Burns, 2007; Carr & Beaver, 2002).

In ancient Greece, in a time when science was defined by the arts and religion, the emergence of new knowledge was considered divine; emergent structures were thought to emanate from a force from above – ‘the one‘ – and understood to be controlled by something outside the person (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999). This hierarchical perspective is similar to the approach humans developed during the middle of Holocene with regard to unknown phenomena. The interesting thing about this approach is that people’s conception of the effect of illumination (their perceptions of emergence) was attributed to external factors.

Johnson-Laird (1996) argues that the French mathematician Jacques Hadamard (1865-1963) was one of the first to comprehend that creative outcomes were caused by implicit mental processes; he considered intra-personal creativity to be explained by unconscious parallel mental processes and mental imagery. According to JohnsonLaird (ibid.), Hadamard was inspired by Einstein, Poincaré, as well as by Wallas’ (1926) four stage model of creativity, which contains preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification. With this conception, focus was put on incubation, a black-box phenomenon that operates in the background of the human mind to create suitable solutions to the problem. The process was suggested to be triggered when attention was shifted away from the actual problem to another task. Later on, illumination was expected; ideas were supposed to emerge, that is, “pop up” into consciousness, possibly, but not certainly, contributing to the resolution of the problem at hand. Guilford (1950) argued that creativity is general to humans and an instance of learning, because its application results in a change in behavior. He discriminated creativity from traditional learning, referring to branches and governments that complain about helplessness among scientific and technical personnel, who could improve their performance on assigned tasks using techniques they had already learned, but who failed on problem-solving when new solutions were required. Guilford referred to Terman and Oden (1947), who followed children with exceptionally high IQs to study various aspects of intelligence, from childhood to adulthood. They first applied the Stanford-Binet scale, but when these children grew up, the researchers also tested for creativity by applying a verbal intelligence test called Concept Mastery test (CMT), which correlated with the Stanford-Binet test (Terman, 1956). The CMT was based on a synonym-antonym test (Otis, 1916) and another analogies scale (no reference given). Terman and Oden argued that intelligence could be determined by the number and variety of concepts at a person’s command, and the ability to see relationships between them. Creativity, on the other hand, they argued, is the ability to make new mental constructs out of one’s repertoire of informational and conceptual raw material. The results concerning the relation between intelligence and creativity, as Guilford put it, were not decisive. Hocevar (1980) examined the relation between ideational fluency and CMT, and his rationale for using ideation fluency but not originality (which is commonly included in the definition of creative outputs) was that fluency was included in many other tests of creative thinking, and logically unrelated to intelligence. The result of the study rejected any relation between intelligence and ideational fluency. In yet another study with a similar ambition, Welsh (1966) studied the relation between intelligence and creativity, using CMT and a version of the Welsh Figure Preference Test called the Revised Art Scale. He also assigned D-48, a non-verbal test composed of two types of test problems using a series of dominoes. The test has proven to be reliable and unaffected by ethnicity or gender, but can to some extent be explained by socioeconomic status (Domino & Morales, 2000). Test outcomes also seem to be related to area of study, for example, engineers typically score high on D-48, whereas philosophers tend not to (Gough & Domino, 1963). Neither of the intelligence tests turned out to be related to creativity. The results of these studies indicate that there are variations in knowledge creation and learning that are similar to the adaptive-generative learning continuum often referred to in the organizational learning paradigm (Hinchcliffe, 1999; Senge, 1990). In this paradigm, adaptive learning – coping within the frame – seems to be consistent with aspects of general intelligence; one can perform with mastery without adding anything new to the process. Adaptive learning is discriminated from generative learning, which is the creation of thoughts and mental constructs outside the subject’s mental frame of reference (Senge, 1990). This is consistent with Terman and Oden’s conception of creativity (see above), as well as with Finke, Ward and Smith’s (1992) proposal that creative cognition is an emergent process, that is, the production of new combinations based on previous concepts of knowledge. According to Baughman and Mumford (1995), the combination and reorganization of present knowledge provide a mechanism for generating new ideas, that is, emergence (Finke, 1996). For example it can be applied by superimposing two images (Rothenberg, 1986). During the second half of the 20th century, models were developed to assess and facilitate creativity, based on the conviction that all people have a creative ability (Guildford, 1950). Brainstorming (Osborn, 1957) was suggested as an intervention similar to goal setting to improve idea generation for creative problem-solving (CPS) (Litchfield, 2008). There are four rules or assignments for brainstorming: (1) to generate as many ideas as possible, (2) to avoid criticizing any of the ideas, that is, to defer judgment (3) to attempt to combine and improve on previously articulated ideas, and (4) to encourage the generation of "wild" ideas. However, in studies comparing group versus individual brainstorming, the effect of group was rejected (Dunnette, Campbell & Jaastad, 1963; Taylor, Berry & Block, 1958). In both studies, people who had previously worked together were assigned to the groups, which, according to the authors, is equivalent to a real life situation. The explanation was that the group situation causes production blocks because only one person at a time is able to give suggestions, which was argued to interfere with individuals’ mental “production train” of thoughts (Kerr & Tindale, 2004). This means that, even though you might have a great idea, your presentation of the idea is blocked by someone else’s presentation, which is assumed to cause inhibition of the mental activities associated with creative processing. These authors suggest that attention should be paid to social cognition in order to understand the complexities of groups as problem-solving units (Larson & Christianity, 1993; Cacioppo & Berntson, 1992). But although there seems to be doubt about the effect of group facilitation on ideational fluency, several versions of the original concept have evolved over the years, and it is commonly used in organizations even today (Isaksen & Treffinger, 2004). According to Simonton (1999), a creative idea or product must be original with respect to a specific socio-cultural group. He exemplifies this with Galileo’s discovery of sunspots. Even though the Chinese had noted their existence for well over a thousand years, it was considered an original contribution to European civilization. “Clearly, an original idea or product is judged as adaptive not by the originator but rather by the recipient. Accordingly, we have another reason for maintaining that creativity entails an interpersonal or socio-cultural evaluation. Not only must others decide whether something seems original, but they are also the ultimate judges of whether that something appears workable.” (Simonton, p. 6).

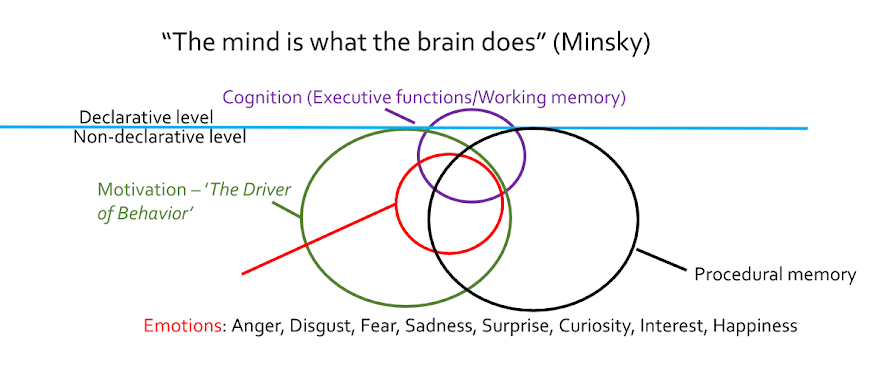

Within the frameworks of creative cognition, Finke, Ward and Smith (1992) suggested the Geneplore model for intentional creativity, which contains two phases of processing: a generative phase with representations of preinventive structures and an explorative phase in which the preinventive constructs are used to form emergent structures. Contrary to Creative Problem Solving, which focuses on group processes, this approach aims at understanding creativity from an intrapersonal perspective, focusing on the production of new mental constructs. Finke (1996) argued that the Geneplore model “can use mental imagery to retrieve various features and incidental details that are not intentionally committed to memory” (p. 382). Seger (1994) proposed that memories that are formed incidentally contain non-episodic, complex information that has been projected into the memory system without awareness through implicit learning. This suggests that it is difficult to control processes involved in forming new constructs of knowledge, independent of whether they have an adaptive or a generative orientation. In studies of emergence, originality emerged from categories that were unrelated to one another (Mobley, Doares & Mumford, 1992; Wilkenfeld & Ward, 2001). Creativity is a complex construct consisting of both novelty (originality) and usefulness. It can refer to the performance, potential, product, or problem-solving (Runco, 2008). It is a general mental ability that is determined by the interplay between different regions (handling both declarative and non-declarative cognitions) in a normally functioning human brain (Damasio, 2005; Fenker & Schültze, 2009; Flaherty, 2004). Within these regions, problem-solving is a matter of automaticized processing, directed by attention; there is a bidirectional influence between processing, based on parallel distribution, and attention. Parallel distributed processing means that units in a system interact by being organized into groups (modules) and interconnected in overlapping chains (pathways) of modules. Processing is based on propagation of activation among the units, which means that a search for interconnecting units is performed in a very broad sense (Cohen, Servan-Schreiber & MCcClelland, 1992). Based on the above, it is possible to conclude that creativity is a novel and original output, based on individual or social cognitive processing in accordance with a connectionist approach.

The emergence of knowledge within the organization

The purpose of an organization is to attain a common goal (Campbell, 1991; Jacobsen & Thorsvik, 2002; Martin, 2001), but according to Isaksen (2007), leaders and organizations are facing an ever-increasing challenge to deal with escalating complexity. Business success seems to be dependent on creativity and the way creativity is managed (Amabile & Kharie, 2008). Organizations should have an orientation toward vitality and change in order to handle, or manage, the complexity within the organization (Baker & Sinkula, 1994; Senge, 1990). These two factors are fundamental to complex problem-solving, and as a consequence, also to aspects of the emergence of knowledge. A vivid and famous example of goal intervention to stimulate knowledge creation is the rescue of the American crew onboard the returning Apollo 13 shuttle in 1970ies. The management at NASA assigned a team to invent a filter to clean the air in the shuttle in order to prevent the crew from being intoxicated by carbon-dioxide. This goal was addressed after one or two of the oxygen tanks had exploded leaving the crew with the prospect of certain death. This is by definition a complex situation, and can be used as a schoolbook example of how to solve other complex tasks. As the story goes, a group was assigned to invent this artifact – the carbon-dioxide filter – by combining things that were to be found on the shuttle. Objects that were previously perceived to be unrelated were used as preinventive structures to form an emergent structure – the carbon dioxide filter. This is in accordance with the creative cognition approach proposed by Finke, Ward and Smith (1992), suggestions about unrelated objects (Mobley, Doares & Mumford, ibid.; Wilkenfeld & Ward, ibid.), as well as with assigned goal setting as an intervention to ignite the motivation to solve complex problems (Litchfield, ibid.). After the goal was assigned, the problem-solving team was left alone, which means that the NASA management assigned another important aspect of inter-personal creativity: independence to attain the goal through decentralization, which is consistent with the suggestion about the bidirectional relation between attention and process in the framework of parallel distributed processes used in the present thesis (Cohen et al., 1992). Eventually, as most people know, the filter was developed within the timeframe, and the crew could return safely to Earth. Even though this is an example of problems that seldom occur, the format is applicable to any kind of complex problem, that is, any product, service or administrative routine in sawmills, pharmaceutical production plants, research and development departments as well as kindergarten schools, universities, farmers cooperatives and so on. Understanding the antecedent processes of a creative outcome – i.e. an idea that is original with respect to a particular socio-cultural group (Simonton, 1999) – on an individual level will help in understanding emergence based on concept combinations on an organizational level. This means that our understanding of knowledge creation within an organization of people could be based on the principles of knowledge acquisition on the individual level, either as perceptions projected into the network of nerve cells in the human brain, or as concept combinations within this network, which eventually will result in the emergence of new ideas (Costello & Keane, 2000; Finke et al., 1992). Such an approach has been applied in the neighboring fields of organizational learning as well as in organizational creativity.

Organizational learning

In the field of organizational development, organizational learning is a framework that aims at understanding how continuous learning processes, preferably generative ones, can be set in motion in the learning organization (Tsang, 1997). Major contributions to the field have been made by Nonaka (1994) and Senge (1990), both of whom suggest models for knowledge creation. In Nonaka’s model, a two-by-two matrix is suggested to describe four possible interactional outcomes between explicit knowledge (things you can verbalize or write down) and implicit knowledge (things that are manifested in gestures and underlying meanings revealed in the interactions between people). Senge (1990), on the other hand, discriminates between adaptive learning (coping within the frame of reference) and generative learning (creating from outside that frame) using a systemic approach – where several aspects work together to form the outcome. Stacey (2007) reviewed and compared the different ways in which organizations change and suggested that several concepts constitute the premises for organizational learning, for example systems thinking and cognitive psychology. According to Lipshitz, Friedman and Popper (2007), the field has developed into a multitude of suggestions pointing in different directions and using a broad array of terminology, such as knowledge creation, systems thinking, mental models, organizational memory and so forth; this marks a detour away from its roots, which are the detection and correction of errors. They demystified the concept by arguing that organizations learn through human interaction, that is, people exchanging knowledge between one another. Maier et al. (2001) argued that the term organizational learning stems from an analogy: “that a goal-oriented social structure, such as an organization, is able to learn like an organism” (p. 14). Although not every suggestion made in the field of organizational learning is equal to the theories developed in the field of organizational creativity, there are more similarities than differences, and it would be wrong not to take them into account.

Organizational creativity

Organizational creativity According to Shalley and Zhou (2008), there are two main frameworks that have guided the work of organizational creativity. The first is Amabile’s (1988, 1996) model, which suggests that expertise or factual knowledge about a given area, explicit or implicit knowledge about strategies to produce creative ideas, and finally, individuals’ attitudes toward a task – the perception of their own motivation to work on the task – are the foundation of organizational creativity. The other framework is proposed by Woodman, Sawyer and Griffin (1993), and stresses that creative performance is predicted by the interaction between individuals’ disposition and work context. The authors proposed that creative performance is a function of, or interaction between, individual (cognitive ability), group (e.g. norms and cohesiveness), and organizational (e.g. culture and reward systems) characteristics. In this latter model, transformation to enhance creativity is the key. The main empirical results suggest that a supportive and stimulating work environment is of great value in promoting creativity within the organization, whereas a non-supportive and controlling leadership style is not (Shalley & Shou, ibid.). This is consistent with the rationale behind Ekvall’s (1996) development of a 10dimensional model operationalized in the Creative Climate Questionnaire (CCQ). The purpose of the CCQ is to assess organizational work climate – the recurrent patterns of behavior, attitudes and feelings that characterize life in the organization – as an intervening variable to the relation between leaders and organization performance (Ekvall, 1996; Isaksen & Ekvall, 2006). An important note is that similar instruments have been developed by Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby & Herron (KEYS; 1996), and Anderson & West (TCI;1996). The climate characters in Ekvall’s model all refer to factors that influence implicit and emotional processes within the individual; for instance, if you feel comfortable enough to express your own opinion in discussions with colleagues, it is easier to think outside the box. Ensuring such a climate is the job of the leader. In a study comparing the effect of leadership style versus work climate on creative outcomes, Ekvall and Ryhammar (1998, 1999) demonstrated that work climate mediates the effect of leadership on the organization outcome.

The neural network analogy

For a creative outcome to emerge, individuals’ dispositions and the characteristics of the organization seem to be intimately interconnected. Some attempts have been made to use cognitive theory to explain organizational behavior. In organization science, analogies to procedural memory systems have been applied in an attempt to explain learning processes (generative and adaptive learning). Cohen and Bacdayan (1994) used analogies to the implicit characters of procedural memory in an attempt to understand the properties and dynamics of how people’s behavior routines arise and change within the organization. This approach helps in understanding how experience, i.e., knowledge, can be rapidly transferred to an appropriate situation. This meanso that when a problem occurs, people with the proper experience will be assigned by the distributed connections of their co-workers to take part in the task of solving the problem. In organizational psychology, neurobiology and connectionist theory have been used with a similar purpose: to describe architectures of knowledge exchange for problem-solving within the organization (Lord and Maher, 1991). According to this approach, complex problems are best solved when the executive function for knowledge creation and development of new strategies are decentralized to the operational level, i.e., when the multiple interconnecting activities within the organization are pursued by independent persons in ways associated with the framework of parallel distributed processes suggested by the cognitive neuroscience (Lord & Maher., ibid.; McClelland & Rumelhart, 1985; Perry-Smith, 2008). Read, Vanham and Miller (1997) argued that, in such interactive feedback systems, knowledge is represented by interaction between many instances rather than by a single instance. Since knowledge is distributed to many instances (persons), the organization is not dependent on any single instance.

The conclusion based on this reasoning is that creative ability or potential within an organization is manifested through inter-personal, or social, cognitive exchange processes in analogy to the PDP framework, which can be triggered by the intervention of a challenging goal.

Stöd gärna bloggen via Swish (Sverige), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

More about my expertise:

Executive coaching for CEOs/managers and workshops to facilitate Organizational Performance, Learning, and Creativity for Problem Solving | Lectures: Nutrition for physical and mental health | Course/lecture: children's emotional and social adjustment and cognitive development | Language training - Swedish | Academy Competency | CV | Teaching skills and experience | Summary of research project | Instagram | Linkedin | YouTube-channel | TikTok | Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment