Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

Today in Helsingfors, I conducted a lecture/talk on Domestic violence, how court personnel (judges) rule to discriminate against children's father relations in custody disputes, and Parental Alienation. Custodial conflicts are typically female, but the lecture also acknowledge that women also are alienated (outliers).

The lecture/talk is for sale if any organization want's to learn more about the topics.

The talk included research about human evolution, early childhood development, and how fragile episodic memory is.

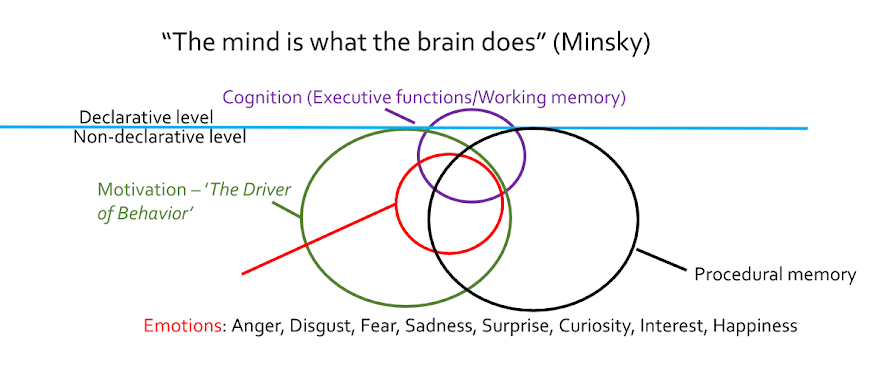

Humans, Homo Sapiens Sapiens, are mammals. That means that we have a reptilian and mammal brain. But on top of that we have prefrontal cortex and something called prospection - the ability to imagine mental models and run them forward in time (Gilbert and Wilson, 2007; Kaku, 2014; Schacter and Addis, 2007). This is normal thinking.

Prospective thinking is based on perception and memory. Perception is stuff we experience in the present by our five senses.

Memory is either declarative or non-declarative.

Non-declarative memory control things like walking, running, dancing, and verbal communication.

Declarative memory is semantic, episodic, or personal semantic.

Semantic memories includes things like numeracy - 2+2=4, and information about geography: Stockholm is the capital of Sweden. Semantic memory is stable over time.

Episodic memory, on the other hand, is very unstable:

“Since the future is not an exact repetition of the past, simulation of future episodes requires a system that can draw on the past in a manner that flexibly extracts and recombines elements of previous experiences” (Schacter and Addis, 2007).This means that episodic memory is vulnerable for social influences - memory hacking (Shaw, 2016).

Cognitive capacity develops at a rapid pace during the first five years of living. Food play an important role as ~60% of the energy consumed goes to the brain (among adults, 20 % of the energy goes to the brain).

But also parental style (Baumrind, 1996) and the communication in the home environment has an impact; kids who experience academic oriented communication in the home can gain up to 30 million word perceptions compared to kids who experience conflicting communication. This is manifested in school performance at 10 years of age (Hart and Risley, 1995).

Between five to twelve years of age cognitive development slow down in favor of social development; this is the time when the child is practicing to interact with other people for the purpose of establishing social networks.

All together, this can be described as emotional and social adjustment and cognitive development. Children who live with both parent or their fathers, have better emotional and social adjustment, and cognitive development compared to children who live with their mothers (Macrae, 2021; Moffitt ett al. 2001; Österberg, 2004).

Physical violence in intimate relationships is evenly distributed between the sexes; women account for slightly more than half of incidence and injuries (Archer, 2000, 2004; Bergkvist, 2002; Bates,2016, 2018; Bates et al. 2014; Bates et al. 2019; Straus, 1979; Thornton et al. 2012).

Lethal domestiv violence will equally unlikely (0.000005) affect children, men and women.

Psychological violence, relational aggression, is typically female.

Overall, the typical perpetrator of intimate partner violence is a woman (Archer,2000, 2004; Bergkvist, 2002; Bates, Graham-Kevan och Archer , 2014; Bates och Graham-Kevan, 2016; Bates, 2018; Bates, Kaye, Pennington och Hamlin, 2019; Crick och Grotpeter, 1995; Thornton et al. 2012).

The likely explanation is Borderline Personality Disorder (Österberg, 2023).

Statistics from Swedish and American courts show that staff (judges) discriminate against children's father relationships in 75% of cases (Elfver-Lindström, 1999; Schiratzki, 2008; Biringer and Harman, 2018).

It increases the risk of parental alienation (Bernet, 2008, 2021; Kruk, 2015; Warshak, 2014, 2015), which occur when a parents, typically a mother, lie to the child about the other parent (typically a father). This process of manipulating the child's mind is referred to as memory hacking (Braun et al. 2002; Shaw, 2016; Spanos et al. 1999; Strange et al. 2006).

The post-marxist feminist movement reject the science on Domestic violence. Instead they use an invalidated concept called men's violence against women. Their rationale for that is partly the work of sociologist Dr. Eva Lundgren and gynecologist Gun Heimer, both promoted to professor at Uppsala University, as well as an organization called ROKS. They published a book that didn't meet demands for validity and reliability (Lundgren et al. 2001). In 2005, Uppsala university banned Dr Lundgren from teaching, a unique decision.

Despite the facts that the typical perpetrator of domestic violence is a women, and that children are better of living with their fathers, social workers in Finland and Swedish apply Lundgren's, Heimer's, and ROKS invalidated approach, instigating domestic conflicts against fathers.

Lundgren's, Heimer's, and ROKS invalidated claims was used by staff working at governments; Berit Jernberg employed by Sweden's Equality Authority (Jämställdhetsmyndigheten) claimed:

When a woman hits a man, it should be classified as men's violence against women

When the conflict instigated by the social worker's reach a court personnel (judges) apply something called the presumption of motherhood (mater semper certa est). The implication is that they (judges) discriminate against children's important father relations in at least 75 % of the cases.

During 2022, a mother, obviously with severe mental issues, had isolated herself with the kids (n=2). This was probably supported by social workers who refused to separate the children from their mother. The mother killed the children and herself by standing in front of the train.

Link to source.

A few months earlier, a similar case occurred in Finland. Finnish social workers ignored a mother's severe mental issues. Instead of seperating the child from the mother, they arranged for them to live togehter in a so called shelter. The mother killed her own child and then herself. Finnish police claim they could fin any evidence point at the social workers!?

For some reason, the link to the article doesn't work anymore.

There was a follow up article:

Link to source.

In that perspective, is it strange that Finland's Minister of Justice Anna-Maja Henriksson (SFP) spreads misinformation about Violence in intimate relationships?

Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

Mer om min expertis:

Executive coaching for CEOs/managers and workshops to facilitate Organizational Performance, Learning, and Creativity for Problem Solving | Lectures: Nutrition for physical and mental health | Course/lecture: children's emotional and social adjustment and cognitive development | Language training - Swedish | Academy Competency | CV | Teaching skills and experience | Summary of research project | Instagram | Linkedin | YouTube-channel | TikTok | Twitter

References

Archer, J. (2000). Sex Differences in Aggression between Heterosexual Partners: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 651-80.

Archer, J. (2004). Sex Differences in Aggression in Real-World Settings: A Meta-Analytic Review. Review of General Psychology, 8 (4).

Baters, E.A. (2018). Contexts for Women’s Aggression Against Men. Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science, 1–15.

Bates, E.A., Graham-Kevan, N. and Archer, J. (2014) Testing predictions from the male control theory of men's partner violence. Aggressive Behavior, 40 (1). pp. 42-55.

Bates, E.A. (2016). Is the Presence of Control Related to Help-Seeking Behavior? A Test of Johnson's Assumptions Regarding Sex Differences and the Role of Control in Intimate Partner Violence. Partner Abuse, 7(1).

Bates, E.A., Kaye, L.K., Pennington, C.R. and Hamlin, I. (2019) What about the male victims? Exploring the impact of gender stereotyping on implicit attitudes and behavioural intentions associated with intimate partner violence. Sex Roles, 81 (1-2), 1-15.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Prototypical Descriptions of 3 Parenting Styles.

Bergkvist, T. (2002). Familjevåld: deskriptiv litteraturstudie samt kvantitativ domstudie. Opublicerad kandidatavhandling i juridik. Uppsala Universitet.

Bergström et al. (2022). Interventions in child welfare: A Swedish inventory. Child & Family Social Work, 28 (1), 117-124.

Bernet, W. (2008). Parental alienation disorder and DSM-V. American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(5), 349–366.

Bernet, W. (2021). Recurrent misinformation regarding parental alienation theory. American Journal of Family Therapy.

Bernet et al. (2010). Parental Alienation, DSM-V, and ICD-11. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 38 (2), 76-187.

Braun, K. A., Ellis, R., & Loftus, E. F. (2002). Make my memory: How advertising can change our memories of the past. Psychology & Marketing, 19(1), 1–23.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66(3), 710–722.

Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2007). Prospection: Experiencing the future. Science, 317(5843), 1351–1354.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60(6), 581–592.

Kaku, M. (2014). The Future of the Mind: The Scientific Quest to Understand, Enhance, and Empower the Mind. Doubleday; First Edition.

Kruk, E. (2005). Recent Advances in Understanding Parental Alienation: Implications of Parental Alienation Research for Family-Based Intervention. Psychology Today.

Lundgren et al. (2001). Slagen dam : mäns våld mot kvinnor i jämställda Sverige : en omfångsundersökning. Brottsoffermyndigheten.

Macrae, G. (2021). In the Absence of Fathers: A Story of Elephants and Men. Beyond These Stone Walls.

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Rutter, M., & Silva, P. A. (2001). Sex differences in antisocial behaviour: Conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. Cambridge University Press.

Rand, D. C. (2011). Parental alienation critics and the politics of science. American Journal of Family Therapy, 39(1), 48–71.

Schacter, D.L. and Addis, D.R. (2007).The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: remembering the past and imagining the future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 362 (1481), 773–786.

Seltzer, J. A., & Brandreth, Y. (1994). What fathers say about involvement with children after separation. Journal of Family Issues, 15(1), 49–77.

Shaw, J. (2016). The Memory Illusion: Remembering, Forgetting, and the Science of False Memory.

Shaw, J. (2017). Understanding false memories: Dominant scientific theories and explanatory mechanisms. In P. A. Granhag, R. Bull, A. Shaboltas, & E. Dozortseva (Eds.), Psychology and law in Europe: When West meets East (pp. 247–261). CRC Press/Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Spanos et al.(1999). Creating false memories of infancy with hypnotic and non-hypnotic procedures. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13 (3), 201-218.

Strange et al. (2006). Event plausibility does not determine children's false memories. Memory, 4(8), 937-51.

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41(1), 75–88.

Thornton, A. J. V., Graham-Kevan, N., & Archer, J. (2012). Prevalence of women’s violent and nonviolent offending behavior: A comparison of self-reports, victims’ reports, and third-party reports. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(8), 1399–1427.

Warshak, R. A. (2015). Ten parental alienation fallacies that compromise decisions in court and in therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46(4), 235–249.

Warshak, R. A. (2014). Social science and parenting plans for young children: A consensus report. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 20(1), 46–67.

Archer, J. (2000). Sex Differences in Aggression between Heterosexual Partners: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 651-80.

Archer, J. (2004). Sex Differences in Aggression in Real-World Settings: A Meta-Analytic Review. Review of General Psychology, 8 (4).

Baters, E.A. (2018). Contexts for Women’s Aggression Against Men. Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science, 1–15.

Bates, E.A., Graham-Kevan, N. and Archer, J. (2014) Testing predictions from the male control theory of men's partner violence. Aggressive Behavior, 40 (1). pp. 42-55.

Bates, E.A. (2016). Is the Presence of Control Related to Help-Seeking Behavior? A Test of Johnson's Assumptions Regarding Sex Differences and the Role of Control in Intimate Partner Violence. Partner Abuse, 7(1).

Bates, E.A., Kaye, L.K., Pennington, C.R. and Hamlin, I. (2019) What about the male victims? Exploring the impact of gender stereotyping on implicit attitudes and behavioural intentions associated with intimate partner violence. Sex Roles, 81 (1-2), 1-15.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Prototypical Descriptions of 3 Parenting Styles.

Bergkvist, T. (2002). Familjevåld: deskriptiv litteraturstudie samt kvantitativ domstudie. Opublicerad kandidatavhandling i juridik. Uppsala Universitet.

Bergström et al. (2022). Interventions in child welfare: A Swedish inventory. Child & Family Social Work, 28 (1), 117-124.

Bernet, W. (2008). Parental alienation disorder and DSM-V. American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(5), 349–366.

Bernet, W. (2021). Recurrent misinformation regarding parental alienation theory. American Journal of Family Therapy.

Bernet et al. (2010). Parental Alienation, DSM-V, and ICD-11. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 38 (2), 76-187.

Braun, K. A., Ellis, R., & Loftus, E. F. (2002). Make my memory: How advertising can change our memories of the past. Psychology & Marketing, 19(1), 1–23.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66(3), 710–722.

Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2007). Prospection: Experiencing the future. Science, 317(5843), 1351–1354.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60(6), 581–592.

Kaku, M. (2014). The Future of the Mind: The Scientific Quest to Understand, Enhance, and Empower the Mind. Doubleday; First Edition.

Kruk, E. (2005). Recent Advances in Understanding Parental Alienation: Implications of Parental Alienation Research for Family-Based Intervention. Psychology Today.

Lundgren et al. (2001). Slagen dam : mäns våld mot kvinnor i jämställda Sverige : en omfångsundersökning. Brottsoffermyndigheten.

Macrae, G. (2021). In the Absence of Fathers: A Story of Elephants and Men. Beyond These Stone Walls.

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Rutter, M., & Silva, P. A. (2001). Sex differences in antisocial behaviour: Conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. Cambridge University Press.

Rand, D. C. (2011). Parental alienation critics and the politics of science. American Journal of Family Therapy, 39(1), 48–71.

Schacter, D.L. and Addis, D.R. (2007).The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: remembering the past and imagining the future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 362 (1481), 773–786.

Seltzer, J. A., & Brandreth, Y. (1994). What fathers say about involvement with children after separation. Journal of Family Issues, 15(1), 49–77.

Shaw, J. (2016). The Memory Illusion: Remembering, Forgetting, and the Science of False Memory.

Shaw, J. (2017). Understanding false memories: Dominant scientific theories and explanatory mechanisms. In P. A. Granhag, R. Bull, A. Shaboltas, & E. Dozortseva (Eds.), Psychology and law in Europe: When West meets East (pp. 247–261). CRC Press/Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Spanos et al.(1999). Creating false memories of infancy with hypnotic and non-hypnotic procedures. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13 (3), 201-218.

Strange et al. (2006). Event plausibility does not determine children's false memories. Memory, 4(8), 937-51.

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41(1), 75–88.

Thornton, A. J. V., Graham-Kevan, N., & Archer, J. (2012). Prevalence of women’s violent and nonviolent offending behavior: A comparison of self-reports, victims’ reports, and third-party reports. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(8), 1399–1427.

Warshak, R. A. (2015). Ten parental alienation fallacies that compromise decisions in court and in therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46(4), 235–249.

Warshak, R. A. (2014). Social science and parenting plans for young children: A consensus report. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 20(1), 46–67.

No comments:

Post a Comment