“Children with separation anxiety have mothers with 60% lower oxytocin” (Field). I added high levels of cortisol and asked Gemini about the interaction. This combination [in mothers] makes it difficult for the child to achieve the attentional control and emotional regulation necessary to engage with and master EF tasks. The child is physiologically primed for a “threat” response rather than a “learn and explore” response, directly hindering the development of the executive control needed for school readiness and general cognitive resilience. 8 pages.

Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

Link to source

Here's what Gemini said:

The relationship between children's separation anxiety and mothers' oxytocin levels appears to be complex, with research suggesting a connection related to attachment and bonding.

Here are some key findings from studies:

Lower Maternal Oxytocin: Some research has found that mothers of children diagnosed with Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD) had significantly lower plasma oxytocin levels compared to mothers in a control group.

Oxytocin and Treatment: In one study, the lower oxytocin levels in mothers of children with SAD increased significantly three months after their children received treatment for the anxiety. This suggests oxytocin may play a role in the etiology (cause) of SAD.

Perinatal Period: Lower oxytocin levels in the postnatal period have been associated with maternal symptoms of separation anxiety and depression during pregnancy, as well as an anxious maternal attachment style. This points to a potential link between oxytocin, maternal emotional state, and bonding difficulties, which can impact the child's attachment.

Oxytocin and Bonding: Oxytocin is often called the “hormone of attachment” and is crucial in mother-infant bonding. It is linked to maternal behaviors like eye gaze, affectionate touch, and responsiveness. Lower oxytocin levels are associated with bonding difficulties.

In summary, a pattern emerges suggesting that:

Lower maternal oxytocin levels may be associated with maternal separation anxiety, anxious attachment styles, and bonding difficulties during the perinatal period.

This biological and emotional context could contribute to the development or persistence of children's separation anxiety (SAD).

13 years ago, I wrote an article about mothers' cortisol levels before, during, and after pregnancy and children's mental health (Österberg, 2012).

Here's what Gemini had to say about it:

The role of maternal cortisol levels (the main stress hormone) before, during, and after pregnancy is a significant factor in the development of a child's stress response system and anxiety, including separation anxiety.

🤰 Prenatal Cortisol (During Pregnancy)

Elevated maternal cortisol levels during pregnancy—often due to high levels of maternal stress, anxiety, or depression—are strongly linked to negative outcomes in the child's developing stress response.

Fetal Programming: Cortisol can cross the placenta, exposing the developing fetus to higher levels of stress hormones. This is thought to 'program' the fetal Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates the body's stress response.

Altered Infant Reactivity: Research shows that higher maternal prenatal cortisol is associated with:

Higher general anxiety symptoms in the child.

Increased infant stress reactivity (e.g., higher cortisol levels in the child when facing a stressful situation).

Increased negative behavior and fearfulness in infancy.

Less habituation to repeated stressors like maternal separation, suggesting an overactive stress response.

Timing Matters: The timing of elevated cortisol exposure during different trimesters may be linked to different developmental outcomes

🤱 Postnatal Cortisol (After Birth)

The mother's cortisol levels and psychological state after the child is born also play a role, often through their impact on the mother-child interaction and bonding.

Postnatal Anxiety: Maternal anxiety and stress in the first few months post-birth are linked to a child's subsequent internalizing difficulties (like anxiety).

Stress Regulation: A lack of positive, supportive, and sensitive caregiving—which can be affected by high or dysregulated maternal cortisol/stress—can disrupt the child's ability to self-regulate their own stress (cortisol) response.

Mother-Child Interaction: High maternal distress and anxiety postnatally are related to:

Worse mother-child interaction quality.

Higher cortisol concentrations in the child during stressful situations (like separation).

🔗 The Combined Equation

Cortisol adds a major biological component to the mother-child relationship equation, strengthening the link between maternal mental health and child anxiety:

Prenatal Exposure: High maternal stress (and thus cortisol) can biologically predispose the child to an overactive stress system, making them more sensitive to anxiety and fear, including separation anxiety.

Postnatal Environment: If the mother's cortisol remains high postnatally due to ongoing stress/anxiety, it can undermine the quality of care and bonding (where oxytocin plays a key role), making it harder for the child to develop a secure attachment and cope with separation.

In essence, high maternal cortisol before and during the perinatal period creates a more vulnerable physiological foundation in the child, and high postnatal cortisol can contribute to a less secure emotional environment, increasing the child's risk for separation anxiety.

Oxitocin and cortisol combined.

This is Gemini's respons:

Research often studies these two hormones (oxytocin and cortisol) together because they represent the balance between bonding/social engagement and stress/threat response, and their interaction has a powerful, combined effect on a child's mental health.

The interactive impact of low maternal oxytocin and high maternal cortisol is hypothesized to create a “perfect storm” for insecure attachment and increased vulnerability to anxiety and other mental health challenges in the child.

🌪️ The Interactive Impact: Low Oxytocin & High Cortisol

1. Impaired Bonding and Increased Stress Reactivity

Low Oxytocin \rightarrow Reduced Bonding Behaviors: Low oxytocin is linked to less affectionate contact, less maternal gaze, and reduced emotional engagement from the mother. This means the mother is less likely to engage in the specific, warm behaviors (like soothing touch or talking about the baby's feelings) that promote the child's developing oxytocin system.

High Cortisol \rightarrow Heightened Stress: High cortisol often reflects underlying maternal stress, anxiety, or depression. This stress:

Prenatally: Biologically programs the child's own stress system (HPA axis) to be overactive, making them more reactive and fearful.

Postnatally: Can lead to less sensitive, more inconsistent, or more intrusive parenting, further contributing to a stressful environment for the infant.

The Combination:

When a child is exposed to high stress hormones (cortisol) and lacks the buffer of bonding hormones (oxytocin) from the mother, the child's own stress system remains highly reactive and dysregulated. The mother is less equipped both biologically (low OXT) and psychologically (high Cortisol/stress) to provide the sensitive, regulatory care the infant needs to feel safe and secure.

2. Disrupted Mutual Regulation

The relationship between a mother and infant is a dance of mutual physiological regulation. The mother's calm presence is supposed to downregulate the child's stress response.

Oxytocin as a Buffer: In typical development, oxytocin is known to inhibit the stress response by decreasing the release of cortisol. When a child is stressed (e.g., during separation), a mother's warm, soothing interaction releases oxytocin, which helps dampen the child's rising cortisol.

The Dysregulation: When the mother has low oxytocin, the natural“ off switch” for the child's stress response is weaker. When she also has high cortisol, she may be experiencing the stress herself, making it impossible for her to act as a buffer. This mutual dysregulation can contribute to:

Anxious Attachment: The infant learns that the primary caregiver is an unreliable source of comfort, leading to an insecure or anxious attachment style.

Increased Anxiety: This insecure foundation makes the child highly vulnerable to internalizing disorders, such as Separation Anxiety and generalized anxiety, because they lack confidence in the caregiver's availability to regulate their distress.

3. Long-Term Epigenetic Changes

Research suggests that high maternal involvement (which is linked to higher oxytocin activity) can positively upregulate the oxytocin receptor gene in the child. The opposite—a combination of low OXT-driven care and high Cortisol stress—may negatively impact the child's developing oxytocin system through epigenetic changes (changes in gene expression).

This means the mother's hormonal profile and resulting behavior could potentially shape the child's lifelong capacity for social engagement, stress regulation, and overall mental health.

In essence, the synergistic effect of low maternal oxytocin and high maternal cortisol deprives the child of both the biological “cushion” and the behavioral reassurance needed to develop a robust, resilient stress-response and social system.

What's the interactive impact of low oxitocin and high cortisol on children executive function during the first four of life?

This is Gemini's respons:

That is a cutting-edge question in developmental psychobiology. The interaction of low maternal oxytocin (OXT) and high maternal cortisol (CORT) during the first four years of life is hypothesized to negatively impact a child's Executive Functions (EFs) by creating a biological and behavioral environment that destabilizes the child's developing stress and regulatory systems.

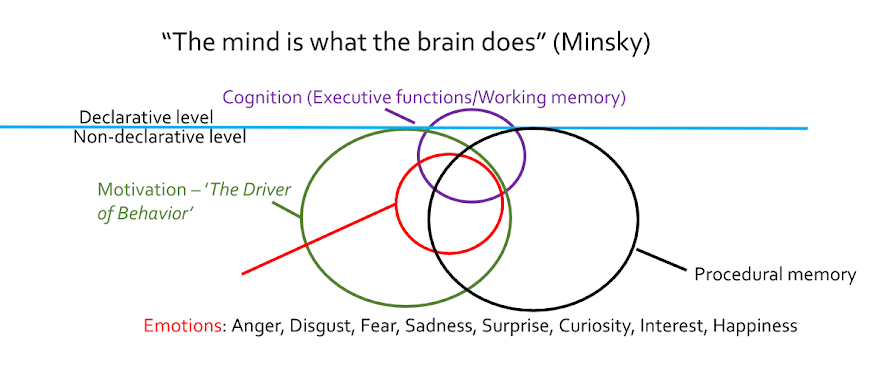

Executive Functions are a set of core cognitive skills that develop rapidly in the preschool years (age 3-5), including inhibitory control (self-control), working memory (holding and manipulating information), and cognitive flexibility (shifting attention).

🧠 Mechanisms of Impact on Executive Functions

The combined low OXT and high CORT scenario influences a child's EFs through two primary, overlapping pathways: Biological Programming and Caregiving Quality.

1. Biological Programming and Stress Dysregulation (High Cortisol)

High maternal cortisol, both prenatally and in the early postnatal period, is strongly linked to deficits in EFs.

Fetal HPA Axis Programming: Exposure to high maternal cortisol in utero can reprogram the child's own Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, the body's main stress response system. This often leads to cortisol dysregulation in the child, making them hyper-reactive or hypo-reactive to stress.

Neurotoxic Effects: Chronic, high levels of cortisol in early life have been shown to have potentially neurotoxic effects on brain regions integral to EFs, particularly the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the hippocampus. These regions are essential for working memory, attention, and impulse control.

Direct Link to Poor EF: Studies show that children with higher, more dysregulated cortisol levels in infancy and toddlerhood often exhibit lower scores on EF tasks (like inhibitory control and working memory) by preschool age.

2. Impaired Interactive Regulation (Low Oxytocin)

Oxytocin is crucial for social bonding and, critically, for buffering stress. Low maternal oxytocin impairs the interactive quality that supports EF development.

Weakened Stress Buffering: Oxytocin acts as a natural antagonist to cortisol, helping to calm the HPA axis. When a mother has low OXT, she may be less likely to provide the soothing, warm, and responsive interactions (like affectionate touch and synchronous play) that would naturally trigger OXT release in the infant and help the infant's own system downregulate stress.

Insecure Attachment \rightarrow Poor EF: Low OXT is linked to less sensitive parenting and less secure attachment. A child with insecure attachment must dedicate more cognitive resources to monitoring the caregiver's availability and managing internal distress, leaving fewer resources available for developing complex EFs.

Reduced Positive Parenting: The low OXT state is associated with reduced positive parenting. Since EFs are often developed through structured, scaffolded play and consistent routines, a lack of these high-quality interactions directly limits the practice opportunities the child needs to unpack and develop these skills.

🎯 The Synergistic “ Unpacking” Deficit

The interaction of \text{Low OXT} \times \text{High CORT} creates a dual deficit:

A highly stressed and vulnerable brain (due to high CORT exposure).

A deficient stress-buffering and learning environment (due to low OXT-driven caregiving).

This This combination [in mothers] makes it difficult for the child to achieve the attentional control and emotional regulation necessary to engage with and master EF tasks. The child is physiologically primed for a “threat” response rather than a “learn and explore” response, directly hindering the development of the executive control needed for school readiness and general cognitive resilience.

Please support the blog via Swish (Sweden), MobilePay (Finland) or Wise.

More about my expertise:

Executive coaching for CEOs/managers and workshops to facilitate Organizational Performance, Learning, and Creativity for Problem Solving | Lectures: Nutrition for physical and mental health | Course/lecture: children's emotional and social adjustment and cognitive development | Language training - Swedish | Academy Competency | CV | Teaching skills and experience | Summary of research project | Instagram | Linkedin | YouTube-channel | TikTok | X

No comments:

Post a Comment